|

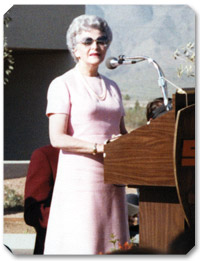

CHAPTER FIVE When Virginia and Ken moved to Arizona in 1972, Maricopa County's population had been just under one million. By 1999, the year of her death, the population had increased to more than three million. The cultural and social needs she encountered upon first arriving multiplied in proportion to the population increase, and from 1975 on, Virginia found herself at the forefront of a new, pioneering philanthropy in Arizona. Looking back over the diverse list of Virginia Piper's contributions from 1975 to 1999, it is nothing short of staggering to realize the full extent of her influence upon the cultural, educational, medical, and religious sectors of an entire county, affecting in turn an entire state, perhaps even the West itself. Over a period of twenty-five years, Virginia funded over a thousand grant requests. Post-widowhood, she chose a path of active selflessness, blooming into a happy, generous, self-actualized woman. Children, education, arts and culture, healthcare and medical research, religious organizations, and older adults became her focus. While these areas of interest had been part of Paul Galvin's earlier charitable initiatives, Virginia devoted herself to these causes, bringing her own unique stamp and approach. What Virginia didn't know, she learned. Her lifelong habit of mind, devotion to study, and work ethic served her well, and it soon became clear to the Arizona community that Virginia Piper's investment in a cause meant the individuals and organizations had been thoroughly vetted and researched. Her reputation as a philanthropist was simply impeccable. Virginia understood, too, the power of her name and how her reputation could benefit a cause. Someone once said, "If it's good enough for Virginia Piper to invest in, it's good enough for me." While Virginia said "yes" to many people and organizations soliciting funds, she never once hesitated to say "no" to proposals she deemed unworthy or unworkable. Virginia saw herself as a catalyst for community engagement. Time and again, Virginia's leadership meant reaching out to other community leaders and using her funds to inspire more giving. Social events, while satisfying for their own sake, also meant, for Virginia, networking, reconnecting with people who could make a difference for Arizona citizens. For example, Virginia adored children. Betsy Taylor, founder of Crisis Nursery, Inc., accompanied Virginia on her first site visit to the nursery, a place of respite for abused and neglected children. A little boy of about three, feeling bold and sensing Virginia's loving nature, went up to her and tugged her skirt. The child was covered with cigarette burns. Virginia reached down and scooped him up into her arms. The two held on to each other. This moment reinforced Virginia's commitment to children and the Crisis Nursery in particular. For years, she underwrote their Annual Gala Benefit and contributed to their fund drives. Virginia knew that abused and poor children needed a safe, nurturing environment in which to play and to build their characters. Prior to the merger in 1991 of the Boys Club and Girls Club, Virginia managed to support both. For the Girls Club, she provided clothes for their thrift shop, sent personal contributions, and gave financial support for a new facility. In 1992, Virginia spearheaded the fundraising by contributing a million dollars to complete a new building that would house the Scottsdale Boys and Girls Club. True to her hands-on involvement, Virginia previewed and discussed plans for the new buildings, fully aware of the need for quality, to serve the multiple needs and interests of Scottsdale children. Similarly, Virginia advanced education and arts and culture in the Valley. She greatly admired Russell Nelson, PhD, a former president of Arizona State University (ASU). The two had a chemistry of vision that flourished during the planning and execution of the Paul V. Galvin Playhouse in the College of Fine Arts at ASU in 1989. Virginia actively assisted in the national adjudication process that resulted in the selection of the internationally known architect, Antoine Predock. Virginia thoroughly enjoyed reviewing all the submitted models for the proposed theater. She was very proud of the project and gave her heart and soul to supporting it. She knew the Paul V. Galvin Playhouse was important to the university and the Valley, and a testament to her loving memory of Paul Galvin. When the playhouse was completed, Virginia had a second portrait of herself painted by Robert Harris and today it hangs in the Galvin Playhouse lobby alongside a portrait of her first husband, Paul Galvin. While Virginia gave one million dollars to create the Galvin Playhouse, records indicate that she contributed to ASU frequently, and the university honored her on several occasions. Virginia's family home had been filled with music, and Virginia never lost her love for live musical performances. She played the organ and the ukulele, and loved to sing harmony. With characteristic flair, she became a terrific arts advocate and enjoyed bringing great entertainers to Arizona. For almost a decade, she underwrote performances for the Scottsdale Center for the Performing Arts (SCPA) Gala. Because of Virginia's generosity, the SCPA Galas reaped exceptional proceeds from these events. Tommy Tune, Bobby Short, Michael Feinstein, Dionne Warwick, and Marvin Hamlisch all came to the SCPA, and Virginia, beautifully dressed, had a marvelous time listening to great talents and visiting with the artists after the show. |

|

| About the Author l Pipertrust.org | |