Happy Christmas, Darling (1944-1959)

Memories

“Miss Rose and Miss Tyler”

In a letter dated September 15, 1924, Cora Higley wrote to her thirteen-year-old granddaughter, Virginia, “Now dear, take your stand and be awake. When you start school, make up your mind to be satisfied and expect to do your work, not because your teacher tells you to but because you want to be a scholar and make your mark in the world. Virginia, I can’t tell you what a brilliant future I think is ahead of you with your many wonderful gifts, but remember, dear, not one of those gifts will ever amount to anything unless you put forth your best effort to unfold them.”

Carol Critchfield, Virginia’s younger sister, fondly recalls a favorite children’s game invented by Virginia in which both sisters placed their combined dolls in rows in an imaginary classroom and pretended to be schoolteachers. Virginia called herself Miss Tyler and Carol, Miss Rose. Miss Tyler and Miss Rose educated their silent little class of pupils, though as Carol describes, “Oh, yes, sometimes they could be quite naughty!”

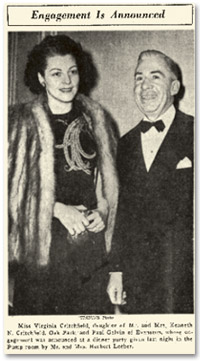

By the time Paul Galvin and Virginia Critchfield met in November 1944, the world was in its fifth hellish year of war. Americans got by on strict wartime rationing, and an unprecedented eight million American women worked outside the home, primarily in secretarial and teaching positions. Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas” was a popular holiday song, the musical Oklahoma! had debuted on Broadway, and Walt Disney’s animated film feature, Bambi, was a box-office smash. Across the Atlantic, underground French Resistance fighter Albert Camus’ novel, The Stranger, was published; the uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto had failed tragically; and leaders from Russia, the United States, and Britain met to strategize the defeat of Hitler’s Third Reich. President Franklin D. Roosevelt would die unexpectedly in 1945; Italy’s fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini, would be deposed and executed; and Adolf Hitler, rather than concede defeat, would commit suicide. In May 1945, six months before Paul and Virginia’s wedding, Germany surrendered. One month later, in June, the United Nations charter was formed, and on August 6 and 9, President Harry S. Truman ordered atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, bringing an end to World War II, which had lasted six years. Over fifty million lives had been lost, and much of Europe was in economic and physical ruin. Ironically, by the end of the worst war the world had ever seen, the American economy was robust, the United States was in possession of the world’s deadliest weapon, and a new era ushered in American prosperity, stability, and global power.

When forty-nine-year-old Paul V. Galvin walked into Dr. Greenwood’s office in the Pittsfield Building on Wabash and Washington in Chicago in the fall of 1944, the medical receptionist who greeted him could never have guessed that this man would transform her future. Nor could Paul have guessed the happiness Virginia would bring him after years of hard-won public success and a steady accumulation of personal sorrows.

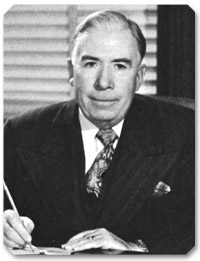

Born in the small farm town of Harvard, Illinois, on June 29, 1895, Paul Vincent Galvin was the son of an Irish bartender, and the oldest of five children. At an early age, Paul showed an entrepreneurial flair, selling popcorn to passengers on trains stopping in Harvard. After dropping out of college because of his family’s economic hardship, Paul joined the army from 1917 to 1919, and on April 24, 1920, he married Lillian Guinan, his high school sweetheart. With a resolute, near-obsessive belief in hard work and the value of plain common sense, Paul started a battery company in Marshfield, Wisconsin. On October 9, 1922, his only child, Robert “Bob” William Galvin, was born. When his battery business failed, Paul joined the Brach Candy Company in Chicago as the personal secretary to Emil Brach from 1923 to 1926.

Recognizing that national radio sales were booming, Paul left Brach to found the Galvin Manufacturing Corporation in 1928 and soon found himself weathering the deaths of his mother-in-law in August 1929, his father on October 3, and his mother on December 9. In the midst of these deeply personal losses came the stock market crash on October 29. Despite all of this, Paul managed to succeed in his ambition to be the first to install radios in automobiles. With his wife Lillian and seven-year-old son Bob, Paul drove to Atlantic City in June 1930 to attend the Radio Manufacturers Association convention. The long drive served as a practical road test for the newly installed radio in his car. Once in Atlantic City, Paul launched his brand-new car radio business with the trademark, “America’s Finest Car Radio.” The word motorola, which would eventually be used in the famous trademarks of Motorola Radio and Motorola, Inc., and which suggested both motion and radio, occurred to Paul spontaneously one morning in 1930, while he was shaving.

The phenomenal success Paul Galvin eventually attained was not without its persistent challenges, failures, and obstacles. Paul, however, had a relentless drive to succeed. He knew how to turn failure into potential inspiration and was fortunate to have the unceasing support of his wife, Lillian, and his brother, Joseph, who both selflessly helped Paul to run his early business with honor, integrity, and efficiency.

In Harry Mark Petrakis’s biography of Paul Galvin, The Founder’s Touch, Paul’s resilient ability to recover from losses and problems and proceed to new success is described in incident after incident. In addition, he treated his Motorola employees, in their initially small numbers and later into the thousands, with fairness and equality, inspiring a legendary loyalty among them and maintaining one of the only American companies whose workers voluntarily refused unionization. His employees could purchase Motorola stock, their healthcare benefits were excellent, and it was not uncommon for Paul personally to make sure an employee or member of his family received proper medical treatment. Paul Galvin inspired unwavering allegiance in his closest friends and employees, and his ethic of hard work, non-defeatism, and fairness, coupled with a kind of sixth sense,a visionary ability to think innovatively and with an eye toward the future, brought him wealth, influence, and a philanthropic reputation.

In Harry Mark Petrakis’s biography of Paul Galvin, The Founder’s Touch, Paul’s resilient ability to recover from losses and problems and proceed to new success is described in incident after incident. In addition, he treated his Motorola employees, in their initially small numbers and later into the thousands, with fairness and equality, inspiring a legendary loyalty among them and maintaining one of the only American companies whose workers voluntarily refused unionization. His employees could purchase Motorola stock, their healthcare benefits were excellent, and it was not uncommon for Paul personally to make sure an employee or member of his family received proper medical treatment. Paul Galvin inspired unwavering allegiance in his closest friends and employees, and his ethic of hard work, non-defeatism, and fairness, coupled with a kind of sixth sense,a visionary ability to think innovatively and with an eye toward the future, brought him wealth, influence, and a philanthropic reputation.

In 1934, he and Lillian purchased a beautiful home at 3038 Normandy Place in Evanston, Illinois, a symbol and testament to Paul’s hard-earned prosperity. Two years later, on a six-week vacation to Europe with his wife and thirteen-year-old son, Paul returned home convinced that war in Europe was imminent. In 1937, the Motorola plant had relocated from its original premises on Harrison Street to a much larger facility on 4545 West Augusta Boulevard, Chicago, where the assembly of home radios commenced. The expanding company was not without its problems, but when Paul’s prediction of a world war was tragically realized in 1939, his company began the extremely successful invention and production of the first hand-held portable communications radio, the Handie Talkie, followed by the longer-range Walkie Talkie. Nearly a hundred thousand units of the Handie Talkie and fifty thousand of the Walkie Talkie radios,a technologically advanced form of wartime communication that played a crucial role in the Allies’ victory over Germany, Italy, and Japan, were produced for the American military.

On the evening of October 22, 1942, Paul faced his greatest loss and emotional crucible when his twenty-year-old son, Bob, walked into their home on Normandy Place to discover that his mother, Lillian, and her maid, Edna Sibilski, had been brutally murdered, apparent victims of a failed robbery. The highly publicized double murder went unsolved, and the distraught father and son moved out of their home and took an apartment at the Edgewater Beach Hotel. Meanwhile, Lillian’s sister, Rose Sturm, helped Paul and Bob try to cope with Lillian’s death. To suffer the tragedy of murder within one’s family is horrific enough, but when it is a high-profile case, the agony is magnified. Paul and his son saw Lillian’s entire life reduced to a violent incident packaged as front-page news. On October 24, for example, the Edwardsville Intelligencer ran headshot photographs of Lillian and Edna Sibilski on the front page, two columns away from a photograph of Eleanor Roosevelt in London meeting with King George VI and Queen Elizabeth.

Tragedy is the most unfortunate, unfair kind of fame, and Paul sought sanity and refuge in his old habit: throwing himself into his work, both as president of the Radio Manufacturers Association and of Motorola. As a result, Motorola continued to thrive in car-radio, home radio, and war-communications production and sales. In 1943, Paul and Bob moved back into their home on Normandy Place, for as Paul said, “It was Lillian’s home, our home. We shared many wonderful memories there.” Further sorrow struck, however, when his brother Joe, with whom Paul had worked closely for so many years in the development of Motorola, died suddenly on March 7, 1944, at the age of forty-five.

Work, by now Paul’s instinctive, embattled response to grief, took the forefront once again, and on May 7, 1945, he presented the Annual Stockholders Report at the Graemere Hotel in Chicago, relaying the status of Motorola, makers of “America’s Finest Radio for Car and Home,” and addressing the postwar “pattern for reconversion of the radio industry back into civilian set manufacture.” He insisted that postwar sales prospects for radios were tremendous and that public interest in television indicated that sales were “ready to go on a commercial basis.” Often prescient in his business acumen, Paul added, “The potential influence of television on entertainment and education in the future prospectively marks television as another industry as big or bigger than the radio-set business ever was, the potential sales prospect is tremendous.”

On the afternoon in 1944 when Paul Galvin introduced himself to Virginia Critchfield, he had suffered personal tragedy, but he was also one of the wealthiest, most powerful entrepreneurs in the nation. One wonders whether Virginia and her family had read the account of the murders in the newspaper and discussed the tragedy or whether she and Paul ever discussed it. One wonders as well whether she knew Paul Galvin as anything more than a name on an appointment calendar and, if she did know, whether it would have impressed her or played any part in winning her affections. Power and wealth affect people differently; for some they are aphrodisiacs, for others a matter of indifference or even antipathy. One might also wonder what intrigued Paul Galvin about his doctor’s pleasant-mannered receptionist. Surely he must have noticed the positive, intelligent personality and good character the attractive young woman possessed. He may even have felt comfortable with her middle-class status, so similar to his own economic origins.

At any rate, in early spring 1945, having spoken with Virginia on several occasions while visiting his doctor, Paul invited her to a play for which he had tickets that same evening. Virginia declined, politely explaining she required the courtesy of advance notice. He soon asked again, giving her a full two-week notice, and this time Virginia accepted.

Paul’s successful courtship of Virginia Critchfield began with dinners, trips to the theater and concerts, or at times just quiet visits with Virginia and her sister on the front porch of their Oak Park home. During one of those evenings, Paul, uncharacteristically shy, confessed to Virginia, “Your company delights me.”

On November 21, 1945, Paul, fifty, and Virginia, two weeks shy of her thirty-fourth birthday, were wed in a quiet ceremony in the living room of Paul’s home on Normandy Place. This marriage, an uncommonly happy union, would last fourteen years, until Paul’s death in 1959. Among the wedding guests were Paul’s good friends, Ed and Hazel Brach; Ed’s brother, Frank Brach; Matt Hickey, director of finance for Motorola; his wife, Naomi Hickey; attorney Charlie Green and his wife, Lucille Green; Father Hussey, president of Loyola University; and Bob and Mary Galvin. Virginia was supported by her sister Carol and her parents, Ken and Jessica.

It is tempting to speculate about how Virginia might have felt, becoming married relatively late and to a widower who had likewise come from humble midwestern stock but who had amassed a fortune because of his own hard work and entrepreneurial genius, a man sixteen years her senior. By all accounts, Paul was charismatic, charming, generous, a terrific raconteur, driven to succeed, and devoutly Catholic. He had great expectations of those around him and was known on occasion, in the context of work, to lose his temper when employees did not live up to those expectations. Paul had one grown son, who became Virginia’s stepson, a daughter-in-law, and later four grandchildren, who would become part of Virginia’s extended family.

To receive the attentions of such a powerful public figure after living a comparatively obscure life as a medical receptionist would have proved a heady challenge for any woman. In addition, Virginia would live in the same home Paul had happily occupied with his first wife, the house where Lillian had been murdered. The emotional adjustment to existence within the context of another person’s life would have required maturity of anyone.

At the moment when her union with Paul became both a legal fact and a spiritual commitment, Virginia’s status was permanently elevated. Socially and economically, she entered the bright-lit arena of public visibility and wealth, with its attendant glamour and prestige, its requisite duties and subtle burdens. Virginia admitted to her new husband that she was shy, but perhaps her shyness was simply a lack of confidence, a quandary about how to measure up, how to live successfully and naturally in a new and rarefied world of privilege she had never known.

The minute she married Paul, Virginia inherited his Swedish live-in housekeeper, Alma Althoff. How did one treat someone like Alma? What was the protocol? How did a former medical receptionist adapt to suddenly having help? The wistful, attractive young woman with the stylishly arched brows in the black-and-white photograph, perhaps dreaming of a more glamorous life than the one she was then living, within a matter of months found herself living a life that met, if not exceeded, those youthful dreams.

Happy marriages fascinate most people by reason of their success. One of the secrets of Paul and Virginia’s happy union may have begun with two gifts they exchanged early in their marriage, nonmaterial gifts demonstrating mutual respect and a high regard for each other’s well-being: Virginia’s conversion to her husband’s faith and Paul’s loyal support and guidance during his wife’s metamorphosis into a new life.

Influenced by her grandmother’s Christian Science tenets, the new Mrs. Paul Galvin now bore witness to her husband’s similar devotion to his Roman Catholic faith. Each night, she watched as this powerful, self-made executive humbly knelt down to pray by their bedside. Nor had she failed to notice how fairly and generously Paul treated his family, friends, and employees. Beyond that, his record of philanthropy was extensive. Observing how genuinely her husband’s faith informed his everyday affairs, governed his decisions, and commanded his values, Virginia made a quiet decision to convert to Catholicism. Without telling Paul, she studied and took the required conversion instruction classes, and at Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve 1948, as her husband rose to go to the Communion rail, he turned to find Virginia standing beside him, smiling, then whispering, “Happy Christmas, Darling. I’m receiving Communion with you tonight.”

As for Virginia’s timidity, partially attributed to social unease caused by her meteoric rise in social status, Paul helped to assuage it by taking Virginia under his wing, standing devotedly beside her at the frequent social functions they attended as Mr. and Mrs. Paul Galvin, seeing to it that she was properly introduced and drawn out, and staying beside her not as a controlling gesture but as a courtesy, an act of nurturance. And just as he had once helped his young daughter-in-law, Mary Galvin, shop for clothes on one or two special occasions to ensure that she had appropriate attire in which she could feel comfortable and therefore confident, he did the same for Virginia. He delighted in shopping for clothes with her at the finer Chicago boutiques such as Martha Weathered and Blum’s Vogue. He taught her how to play the more popular upperclass games of the day (golf, poker, and bridge), understanding how familiarity with these would build her self-confidence and sense of belonging in new social circles. That a man as busy as Paul Galvin, as focused and disciplined as he had to be to run Motorola, would take the time to help his wife become comfortable and self-assured is a marvelous testament to their marriage.

Paul encouraged Virginia to shine. As she became more poised and confident, he looked for opportunities when she might speak at a formal dinner or at a podium, helping her to develop speaking skills previously unimaginable to Virginia. Such thoughtfulness attests to Paul Galvin’s character and provides an understanding of Virginia’s deep and lasting love for a man years her senior, a man dedicated, in his quiet and tactful way, to helping her cultivate the bright grace and social poise for which she would be renowned and remembered. A man known for his appreciation of women’s intelligence and business aptitude, Paul considered his wife an equal partner, a smart woman perfectly capable of her own achievements and success in life. Coming from a similar modest background, he may have identified emotionally with her innocence regarding wealth, as well as with her pleasure in acquiring an upper-class taste in clothing, food, and activities, a pleasure no doubt sharpened by living through the privations of the Depression and the war. Paul must have derived great satisfaction from giving his new wife things she had never dreamed of owning, sharing luxuries and pleasures that neither of them, as children and young adults, had ever enjoyed.

The nonmaterial gifts Paul and Virginia exchanged early in their marriage,Virginia’s conversion to Paul’s faith and Paul’s steadfast support of his wife’s abilities, demonstrate one of the themes of this biography, that each of us is made greater by those who love us ideally and with an eye toward the manifestation of our individual gifts. Problems that might have arisen from Paul and Virginia’s initial economic and social disparities were overcome with mutual respect and love. The potential handicap of Virginia’s shyness or lack of confidence was overcome both by Virginia’s will and by Paul’s gift of support early on and at every turn. This quality of love, based on respect and thoughtfulness, would be a signature trait of Paul and Virginia’s lasting, splendidly happy union.

At the time of their marriage in 1945, Paul’s only son, Bob, then twenty-three, had already wed Mary Barnes. Since Lillian’s tragic death, father and son had shared an increasingly close relationship and business association,with Paul continually giving his son greater responsibilities at Motorola,so it seemed perfectly natural that on occasion the four of them, Paul, Virginia, Bob, and Mary, would socialize, as described by Bob Galvin:

I knew Virginia as she was being courted by my father; we went on double dates together, so to speak, my wife and I, Virginia and Paul. The four of us would go to a golf game or to some theatrical or social event. We didn't always play together; we weren't playing bridge, gin rummy, and eating meals together with undue frequency. But my wife, Mary, who was a younger woman than Virginia, struck it off very nicely with her, and we both thought Virginia was a very nice young lady.

On his father’s first wedding anniversary, Bob and his wife sent a telegram to the Roosevelt Hotel in Chicago, where Paul and Virginia were celebrating:

This is a very wonderful day for the Galvin family. Mary and I want to congratulate you on your first anniversary. We want you to know that the happiness you have radiated during this past year has added immeasurably to the happiness of our lives.

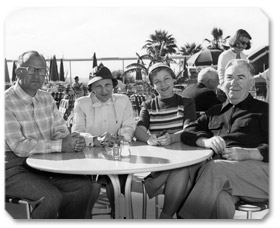

at Camelback Inn, Paradise Valley, Arizona

However quiet and simple it may have appeared, Virginia’s wedding represented no ordinary union. The ceremony itself marked a dramatic rite of passage from one manner of life to another. Matters of etiquette, fashion, and personal conduct in “polite society” must have become suddenly essential for Virginia to learn. To Paul’s credit, he recognized her need for enhanced social poise in this new and unfamiliar environment, and to Virginia’s credit, she worked assiduously to attain the level of conscious dignity and social poise she would become so highly respected and deeply admired for. For example, she would buy and read etiquette books and was known to regularly study the dictionary to increase her vocabulary. She possessed a writer’s sensitivity, using the appropriate word for the right occasion; her hundreds of handwritten letters, which people were loath to discard, are proof of this skill. She understood that the true foundation of etiquette was not elitism but courtesy, and Virginia elevated courtesy to an art form. She was an autodidact, interested in everything from finance, social etiquette, and the rules of gamesmanship to psychology, spirituality, and the arts. She enjoyed life immensely, a tribute to her upbringing, and this, too, was part of her charm and her presence, perhaps part of what Paul Galvin first saw in her. Virginia was not an ornament, a “trophy wife.” Though she was bright, beautiful, and younger by sixteen years, Paul never saw or treated her as anything less than a full and equal partner in his life.

Bob Galvin describes their partnership in the following passage:

Gail, Mary, Michael, Christopher, Robert and Dawn

One of my father’s qualities, and it was a remarkable quality, I suggest it was a distinctive quality, is that he was a man’s man, but he could think like a woman. Very few men can think like a woman.

Now what do I mean by thinking like a woman? He could imagine what must be going on in a lady’s mind and then, because he was sensitive, could be constructively responsive. He understood women more than any man I knew. He encouraged Virginia’s natural achievement; it was not a Pygmalion type of relationship. He’d boost her along, quietly, modestly explaining things to her. And Virginia was a fast learner, and she did things for Paul, too. These were two individuals who enhanced one another’s stability and growth. My father was a great supporter of women; he lifted the women he knew. So although Virginia was a succeeding, achieving human being on her own, she was also well supported first by a great mother and father and then by her husband, my father.

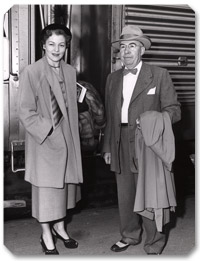

The Galvins made annual winter visits to Phoenix beginning in 1949, when the first Motorola research and development facility was established on North Central Avenue in Phoenix. With twenty employees led by Dr. Daniel Noble, the site would expand and, by 1978, include five affiliated semiconductor facilities in Mesa, Chandler, Tempe, Scottsdale, and Phoenix, with over twenty thousand local employees.

On their winter jaunts to Arizona, Paul and Virginia stayed most often at the nearby Camelback Inn, enjoying parties with friends and family, golfing, and horseback riding, all the sun-drenched pleasures Arizona offers to people subject to interminable winters in the Midwest. Built in 1936, the Camelback Inn was an adobe-style, latilla-beamed resort set at the base of Mummy Mountain in Paradise Valley. Early guests included William Boyd of Hopalong Cassidy fame, Jimmy Stewart, Bette Davis, and Clark Gable. At the time Paul and Virginia stayed there, Camelback Inn was perhaps Phoenix’s premier resort, and in time, Bob and Mary Galvin and their children, Paul’s brother Raymond “Burley”, his sister Helen, Virginia’s parents, and Carol Critchfield and her son Paul were all coordinating winter visits to the resort. The two extended families, the Galvins and Critchfields, would always remain closely connected to Paul and Virginia. Arizona was becoming a welcome gathering place, as well as a fast-growing Motorola development site, for the extended family and friends of the Galvins. Because of their many visits to the state, Virginia would later choose Arizona as her permanent home. Paul and Virginia’s wonderful memories of Arizona eventually led Virginia to make Maricopa County the fortunate recipient of her diverse and magnanimous philanthropy.

In 1946, Bob and Mary Galvin had their first child, a daughter named Gail, adding Dawn in 1949, Christopher in 1950, and Michael in 1952. Until they moved to their four-hundred-acre farm in Barrington, Illinois, in the late 1950s, the growing family lived in Evanston, not far from Paul and Virginia’s home on Normandy Place. Visits to the younger Galvin household were frequent, particularly on holidays and Sundays. When the Galvin children were small, Christmas Eve and Christmas Day were always celebrated at Bob and Mary’s.

Bob Galvin offers the following memories:

We saw my father and Virginia just enough, just enough for Virginia. She had a family, her marvelous mother, father, and sister, and here she came into this family, the family of this man who had one child and four grandchildren, and what was her role in that? Was she going to become the new surrogate mother? No, that wasn't necessary. We were all grown up, Mary and I, so we saw them just enough, once a week or once a month, but always with great cordiality. It was an immediately pleasing relationship.

Virginia was a decent, quiet, respectful, bright person, generous in spirit toward my father. That won us all. There was no discord about Virginia. She never did anything to cause difficulty, and she never presumed anything. She did not try to recast the culture of our family. She was nicely fashioned as a human being, and she had her own wonderful family, too. That was one of her strengths, that her family was very much accepted by ours, everybody liked Ken, Jessica, and Carol, so bringing this other cadre into our family was a nice fit. Both families were comfortable with one another. It was a marriage of kin, of families. The two families formed a substantial, enhancing ensemble, and Virginia stood out as the centerpiece.

Mary Galvin recalls those days, when Paul and Virginia were always together, deeply in love and devoted to each other. Virginia, she recalls, seemed a bit reserved and shy, perhaps unused to the rambunctious nature of a household with so many high-spirited children. After a visit from Paul and Virginia, Mary would invariably ask her children why they had acted up so when they were normally such good children. Their roundabout but charming answer was that this was their way of trying to break through their step-grandmother’s reserve, to get her attention. Today, Gail, Dawn, Christopher, and Michael remember Virginia from the perspective of children. Though she was still a relatively young woman in her thirties and early forties, Virginia is remembered by the oldest, Gail, for her “beautiful handwriting, artistry, and way with words. I wanted to emulate her handwriting,” said Gail. “First just the artistry itself, later the substance of who she was. We probably scared her, four active children in the house. She had a lovely timbre to her voice, a very unusual voice, pleasant and lyrical. She was beautiful, stately-looking, and very impressive to me. I think she upheld being a lady, in the true sense of the word, as a goal. She personified dignity to me.”

Dawn, second of the Galvin children, remembers a “very beautiful, strict lady, a lady of the old-fashioned school” whom she had always wanted to emulate. “She was very soft-spoken but used big, hundred-thousand-dollar words, constantly improving her vocabulary. She always looked perfect and was very disciplined; she had her list of accomplishments set out for the day, and she never failed to achieve each of them.”

Christopher Galvin, the third born, offers the following description of his step-grandmother:

She was very nice, very gracious, and very warm, a grandmotherly figure, a handsome woman, soft-spoken, quiet, engaging, always interested in one's activities, and sensitive and embracing of young people, whom she enjoyed. She was a classic, first-class kind of grandmother figure, always present at our events. Paul passed away when I was nine, in 1959, so I mainly knew them together from the vantage point of grammar school and kindergarten. Like Paul, Virginia was always interested in your grades, your projects, always accommodating of the little entrepreneurial things. One story Paul used to tell about me when I was young is how I wanted to have my own paper route. I would go around the house picking up magazines and trying to sell them. Paul would buy one, and he and Virginia would always humor me.

Michael Galvin, born in 1952, when his grandfather and Virginia had been married seven years, also remembers his step-grandmother. “She was adored and respected by Paul, warm, welcoming, always a part of our family in the traditional sense of holidays, Thanksgiving, Christmas, Easter, birthdays.” He recalls sitting on her lap and opening gifts and her formal style of dress. He never saw her in a bathing suit, bathrobe, or shorts; she dressed in an understated, refined way. Looking back, he realizes how superbly she navigated between her professional world as Mrs. Paul Galvin and her role as grandmother, how important a figure she was in forming his own view of women as strong and fully substantive in their professional bearing but also feminine, graceful, and beautiful.

Virginia’s relationship with her parents, Ken and Jessica, continued to be unusually close even as her own status dramatically altered. Ken now earned a comfortable income in refrigeration engineering for large buildings in Chicago, while Jessica continued to enjoy playing the hundreds of songs she had memorized from her days as an accompanist for silent movies. The Critchfields enjoyed an unpretentious, middle-class lifestyle, and Virginia never failed to invite them to social functions she thought they would enjoy. Indeed, throughout her life, even when her visibility as a philanthropist grew, she consistently welcomed them into her own very public life, a tribute to her loyalty and upbringing and a demonstration of pride in her own background.

Virginia maintained a cordial relationship with her stepson, his wife, and their growing children. She also attended a constant round of gala events, charity balls, black-tie affairs, and corporate functions, activities required of the wife of the president of Motorola. To her credit, Virginia was a quick study, interested in her own self-improvement. Inquisitiveness was one of the driving elements of her personality, whether it was curiosity about how something worked or a genuine, warm interest in other people. And being married to a man like Paul Galvin, there was much for Virginia to learn just to keep up with his constant ambition to build upon previous success and never grow complacent. Paul’s ethic overlapped into a life ethos: never sit still; keep moving. Living with a man like him must have been stimulating, challenging, energizing, and occasionally exhausting; any inclinations toward learning Virginia already possessed had to have been, in the Galvin household, heightened and encouraged.

Quite simply, Virginia adored Paul as much as he adored her, and she wanted him to be proud of her. Whether observing appropriate protocol within the higher echelons of Chicago society or being by Paul’s side at family holidays, maintaining close ties with her own family, or creating new interests in Arizona, Virginia, always a “detail person,” strove to be gracious, to be as knowledgeable and devoted in her manner and bearing as she could. And by all accounts, according to the recollections of those who knew her, she succeeded. Paul’s son describes Virginia’s hallmark qualities as he knew them in those days:

My father, being twenty [sic] years older, was a far more mature human being: he had lived a significant life and had learned by doing; he was gifted in many ways and was constantly improving himself. Virginia, in comparison, had lived a slightly more sheltered life. So when these two came together, you could ascertain the differential. What you saw was a lady of fine qualities. She had worked at a doctor's office and was a professional lady doing admirable work that required organizational abilities. We were impressed that she'd had a good profession. But I don't think she'd had very many broadening experiences. She had decent experiences, her mother, father, and sister were very decent people, but with my father there came a different engagement with life.

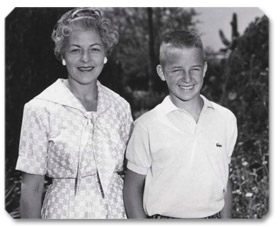

In 1945, the same year Virginia married Paul, Carol Critchfield, who had been earning a living as a fashion and children’s book illustrator, married Arthur Irwin Jirka, an accomplished pianist and captain in the U.S. Army Dental Corps. Their only child, Paul, named after Paul Galvin, was born on September 24, 1946. “Little Paul,” a precocious, ebullient child nicknamed “Smiley” by his friends, would grow up to be naturally gifted in music and athletics. His Aunt Virginia, who had no children of her own, cultivated a deep and loving interest in her sister’s only child. In 1949, Carol, Arthur, and their son moved to Riverside, Illinois, where Paul’s earliest memories of his “Aunt Gin” are of a wonderful, loving lady with a sense of decorum and great strength of character. Though Carol and Arthur divorced in 1955, when Paul was in the fourth grade, Carol and her son continued to live in the comfortable two-story home in Riverside, which Paul and Virginia had built for Carol and Arthur upon Arthur’s return from the war. Divorce in the ’50s was not as easily received or tolerated as it is today. There was still a certain stigma attached to the notion of a divorcee, which, in addition to Carol’s slightly bohemian-artist personality, must have roused protective instincts in her older sibling. In fact, Carol would often refer to Virginia, or Gin, not only as her best friend but also as her “protector.”

Paul and Virginia generously helped Carol financially, so that as a single mother she could continue to use her talents as a children’s-book and fashion-industry illustrator and to teach art classes, thereby earning a living through her artistic gifts,and Virginia frequently made the fifty minute drive from her home in Evanston to visit her sister and nephew. Following his mother’s divorce, Little Paul’s chief male role models became his uncle, “Big Paul,” and his maternal grandfather, Ken.

Riverside, “The Village in the Forest,” was the first planned suburban community in America, a retreat designed for businessmen who could make the twenty-minute train commute into downtown Chicago each day and return to the peaceful, idyllic community designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, the landscape architect who designed Chicago’s Columbian exhibition as well as Central Park in New York City. Originally an area of Indian trails along the banks of the Des Plaines River, then of wooden roads in the 1850s, Riverside, with the advent of the railroad, became a commuter community, boasting its own train station, water tower, America’s first indoor shopping mall (the Arcade Building), village hall, library, ice cream parlor, swinging suspension bridge across the Des Plaines River and winding streets shaded by oak and elm trees. With plenty for children to do,skating on Swan Pond, sledding down Suicide Hill, and participating in Cub Scout activities and Little League games at Indian Gardens baseball field,Riverside afforded its children an old-fashioned, Norman Rockwell sort of childhood, and Paul Critchfield lived there from age three through his college years. According to longtime childhood friend, Ron Milnarik, now a dentist and teacher of dentistry at the University of Illinois Dental School, “Riverside was like a little train set village, where forty cents could buy you a model car kit, and you could go to Victory Lanes, a six-lane, pine-paneled bowling alley, and bowl three games for a dollar on Saturday mornings.” Nestled in its forest of ancient oaks, maples, and elms, Riverside provided children a rare oasis of adventure and safety. Paul Critchfield remembers his own childhood as enchanted, with visits from his Aunt Gin, whether to attend one of his Little League games, to bring gifts at Christmas, or to simply drop in, adding to the magic.

Jean Turnmire, Ron Milnarik’s sister, now an equestrienne and music teacher in Chicago, recalls the many, many times she visited the Critchfield home, where she was first introduced to Virginia, a woman whose kindness, personality, and style easily inspired emulation in young girls. Jean Turnmire was no exception. As she recalls, “Virginia had a tremendous presence. The room would light up when she walked in. She was so gentle and kind and had a wonderful spirit that just glowed.” Jean, who was a year younger than Paul, often stopped by the Critchfield home after school, where she was always welcomed as part of the family.

I lived two doors down from the Critchfields, and I remember that Carol always had WFMT, the public radio station, on in her studio. It was the first time I had ever heard public radio. She would hold studios for small groups of other women artists. It all seemed very modern. They would paint to classical music, Tchaikovsky, for example. It really opened my eyes as a child, the cultural influence in art, music, even food, I had artichokes for the first time at their home.

Jean also recalls being invited to stay over at Virginia and Paul’s home in Evanston on one occasion:

I remember her wonderful maid, Alma, and how it was the first time I ever saw fresh-squeezed orange juice. Virginia introduced me to a lot of new things. My father was a dentist, and we had nice things, too, but Virginia had such elegant taste. When I was in high school, she started giving me Estée Lauder compacts in beautiful gift packages. She was so sweet, and I looked up to her as the ideal lady. I even started dressing like her a little bit, with little scarves like she wore and a Chesterfield coat when I was in high school.

I never heard Virginia raise her voice for any reason. She was unflappable no matter what. I remember years earlier, for example, when she had a new car, a white convertible. It was the first time I had ever used a seat belt, and we all went to get ice cream cones. When we went to get out of the car, I had forgotten to take off my seat belt and my ice cream went flying all over the new car. Virginia just laughed.

I knew Virginia for more than fifty years, first as a child, then as a young woman, and finally as a married woman. Her sister Carol, Paul's mother, was a redhead, always perky, short, bouncy, fun. By contrast, I remember Virginia as tall and elegant but never less than warm. She would float into a room; she had such grace, such elegance. You couldn't find a better person anywhere. Virginia was the ideal of a perfect lady.

So while there was a professional, public side to Virginia, she also possessed, as Mrs. Paul Galvin, a private, personal side that so many remember with great fondness.

Years of marriage to Paul and loving attachments to friends and family gave Virginia the core strength she needed to navigate the difficult last phase of her marriage, when Paul fell terribly ill. She would prove a steadfast comfort to him, and much of her strength derived from the love and support of the Galvin and Critchfield families, who surrounded and supported her through the most difficult time of her life up to that point.

In May 1958, Paul, concerned about black-and-blue marks recurring on Virginia’s arms, took her and their good friends, the Vincent Sills, to the Greenbrier hotel in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, to visit the famous health clinic there. Paul knew such marks were a potential sign of leukemia and wanted to have Virginia tested. As a matter of course, he had his own health checked, and ironically his tests, not Virginia’s, came back with a possible though inconclusive indication of leukemia. In June 1958, after their return to Chicago, Paul, feeling unwell, entered Saint Francis Hospital to have more extensive tests. This time, the diagnosis of leukemia was confirmed.

Dr. Philip Sheridan, a former World War II naval aviator, now a general surgeon, had become friends with Paul and Virginia through his wife, B. J., Mary Galvin’s sister. Phil, who became Paul’s attending physician through the weeks and months of his final illness, recalls the day he was sitting in his small office on Central Street in Evanston when the front door banged open, and Paul, striding in, dropped a piece of paper on his desk, pointed to it, and gruffly asked, “What about this?” Paul was referring to his diagnosis of subacute lymphatic leukemia. As Phil explains, “It was one of those incidents in life that you never forget.”

This was before any chemotherapeutic agents of any significance had been developed. I got hold of Dr. Schwartz, one of my mentors who was by then head of hematology at Cook County and at Northwestern. He gave Paul one year to live from the time of diagnosis.

The more I knew about Paul, the more I respected him. He was quite a man and showed a very serious concern for other people. He knew how to run Motorola and how to respect his employees. I even took care of a number of his employees for him. He was one of the very significant human experiences of my life. I've had the opportunity to meet a lot of great people, and he was right up at the top.

Describing Virginia during this time, Phil said, “She was very detail-oriented. I would go over to their house to check on Paul, and I wouldn’t get out of that house until she had it all figured out exactly what I wanted her to do, in specific terms, in caring for Paul. Both Virginia and Paul were gracious, good people, possessed of honor, integrity, and loyalty.”

For the next eighteen months, with Virginia devotedly at his side, Paul would fight his prognosis valiantly, with intervals of seeming success. He insisted on traveling with Virginia to Arizona, hoping the desert climate and relaxation they had always enjoyed there would give him strength. Paul and Virginia also visited his son and family on their new farm out near Barrington and in September 1959 would insist on hosting a surprise fiftieth wedding anniversary party for Virginia’s parents. But his health quickly worsened after that, and Virginia took on an even greater role as his constant, devoted companion, doing whatever would lift his spirits, even bringing his favorite home-cooked foods to the hospital in those final weeks. Finally, on November 5, 1959, in room 219 of Saint Francis Hospital, with Virginia, his son, brother (Burley), and sister (Helen) by his bedside, Paul Vincent Galvin passed away at the age of sixty-four. Thirteen years old at the time of his uncle’s death, Paul Critchfield remembers Big Paul as “a man with a terrific voice, big Irish eyebrows, and a great dynamic presence.” Paul Galvin’s son, Bob, says, “I had such respect for my father. I didn’t know anybody who was as good as he was. He was just a remarkable man.” The following formal obituary appeared in an official Motorola news release dated November 6, 1959:

Paul V. Galvin, chairman of the board and founder of Motorola, Inc., died yesterday evening (November 5) of leukemia at Saint Francis Hospital in Evanston, Illinois. Mr. Galvin's funeral will be on Monday, November 9, at 10:30 a.m. at a Requiem High Mass in the Holy Name Cathedral, State and Superior Streets, Chicago. Interment will be at All Saints Cemetery, Des Plaines, Illinois.

Paul Galvin had enriched and transformed Virginia’s life in marvelous ways. Now, at his death and by her own choosing, she was left in charge of the Paul V. Galvin Charitable Trust. His charitable works had been extensive, yet a number of his philanthropic projects and dreams remained unfinished. Before his death, Paul explained to Virginia that those projects could easily be turned over to trusted advisors of his choice, and she would never need to be concerned with such a heavy responsibility. Or, if she chose, and only if she chose, she could elect to carry out his unfinished philanthropic work. Paul’s sole concern was for Virginia’s happiness, so he was adamant that the choice be hers. Virginia’s decision to honor her husband’s memory by completing his philanthropic work was unequivocal. Of her own volition, Virginia, upon being widowed, embarked upon a forty-year career as a philanthropist. She began by completing Paul’s unfinished charitable works and in the process learned and mastered the art of philanthropy. In a final act of mentorship, perhaps realizing how much this would give his wife a sense of purpose after he was gone, Paul instructed Virginia in the details and protocol of philanthropic work.

Within days of Paul’s death, the next phase of Virginia’s life began. Learning to administer the Paul V. Galvin Charitable Trust as cotrustee with the Harris Bank of Chicago, Virginia became responsible for decisions about future recipients of the trust. As chief administrator, she would direct millions of dollars to scores of charities in the Chicago area and later in Arizona. After the Galvin Charitable Trust expired, Virginia would establish a trust in her own name. At Paul’s death, however, there was the grieving, the comfort of friends and family, and the ordinariness of life, which returned with a searing loneliness. The man who had loved, mentored, delighted in, and deeply inspired her was gone, but Virginia would maintain her connection to Paul for the rest of her life, in part by emulating those qualities that had drawn her to him in the beginning: his Catholic faith, habits of hard work, and selfless dedication to the well-being of others. By following in Paul Galvin’s footsteps, Virginia learned, in time, to forge her own path.