My Sweet Embraceable You (1969-1975)

Memories

There was never a birthday, anniversary, or special occasion that wasn't marked by a handwritten note from Virginia. Her entire life, excluding the year before she died, Virginia sent out hundreds and hundreds of handwritten cards, including Christmas cards, with the most beautiful, elegant, gorgeous handwriting you ever saw. If you remembered her birthday, you'd get a two-page handwritten thank-you letter back. She had a definite system: at the beginning of every month she would organize all her cards and put a date where the stamp went so that the cards were always on time, always personal, always arriving on the exact date.

Jean Turnmire, longtime friend

Paul Critchfield remembers his first project with his Aunt Gin, in which she introduced him to the joy of giving to others. Paul was a student at the University of Tampa, built in 1891 as a beautiful winter resort once hosting Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders, Sarah Bernhardt, Babe Ruth, the queen of England, and other celebrities. Each room was decorated in a different American tradition, and Paul helped Virginia select one of these rooms, now a classroom, to restore and renovate. This $3,000 project, the result of a proposal they had coauthored, this “little lesson in philanthropy,” helped Paul see firsthand the far-reaching effects of philanthropy upon individual lives. Virginia invited her young nephew to dedications of buildings and groundbreaking ceremonies at Saint Francis Hospital, Loyola Medical Center, and Northwestern University. Whatever the occasion or institution, those early days for Paul were formative, demonstrating what one individual with a will to do good for others can achieve and how the world can be changed for the better, one philanthropic gift, one kindness, at a time.

The closing year of the tumultuous, electrifying ’60s saw the maiden flight of the French-British Concorde, Golda Meir sworn in as Israel’s fourth prime minister, U.S. war deaths in Vietnam surpassing those of the Korean War, student antiwar protests reaching their height with nationwide demonstrations against the Nixon-Agnew war policy, and on July 20 the landing of the Apollo spaceship on the moon, 600 million people worldwide watching as Neil Armstrong standing on the lunar surface said, “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” Motorola had been NASA’s key supplier, providing the communications equipment needed to make that miraculous, historic transmission back to Earth. One month later, in August 1969, the Woodstock Music and Art Festival was held on a dairy farm in upstate New York, where nearly half a million young people gathered during that famous “summer of love.” A decade that had included President John F. Kennedy’s Camelot vision and subsequent assassination; massive antiwar protests; the rise of civil rights, feminist, and youthful countercultural movements; and the tragic public assassinations of two other iconic American figures, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy, came to an end. Two months before his own assassination, Robert Kennedy spoke out against the murder of Martin Luther King, Jr.: “What we need in the United States is love and wisdom and compassion toward one another and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our own country, whether they be white or black.” On November 15, 1969, two hundred and fifty thousand war protestors marched on the Capitol in Washington, D.C. One week later, U.S. astronauts made a second landing on the moon.

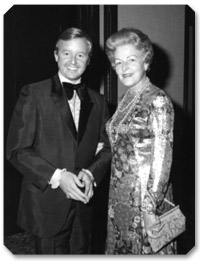

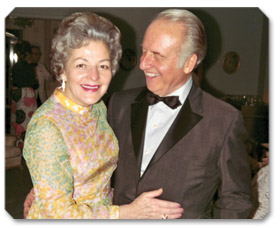

In this national context of deep political and cultural unrest, on December 30, 1969, Virginia Galvin, fifty-eight, married Kenneth Piper, sixty-two.

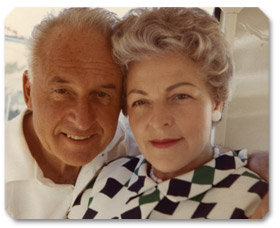

Ken, like Virginia, was a devout Roman Catholic, and throughout their marriage, he served as a deacon and eucharistic minister at the Casa. Ken and Virginia had also both been midwesterners, childless and widowed, and shared a long history with Motorola, Inc. These commonalities would have been a comfort to Virginia, helping to form a solid base of shared experience on which to build a second marriage and stable partnership. The fact that Ken was a dynamic, ruggedly handsome, and charming man would have been important to Virginia, too. Anyone carrying the burdens she had carried on her own for the past ten years would likely be willingly swept off her feet by the courtliness, dash, and sheer vitality of a man like Ken Piper.

Marriages are blended compounds of chemistries and temperaments. Virginia’s marriage to Paul had been marked by a spirit of loving mentorship and graceful progression into a poised maturity. Her marriage to Ken was characterized by his gift of a certain natural, irresistible leisure, a gaiety that offered Virginia the opportunity to relax and simply be herself. She had deeply loved Paul and learned from his example; she had worked conscientiously to carry out his unlived dreams; she had embarked upon philanthropic projects of her own, dated other gentlemen, and traveled the world. Now, with Ken, she could come home and find not only simple rest and happiness but a source of tremendous support and strength in her work.

In her mid-fifties, Virginia was an astute, confident business woman, a spiritually motivated philanthropist, but she was also,by temperament and particularly in her personal life,deeply romantic in her tastes. To surround herself with an atmosphere of beauty and serenity was crucial to her sensibilities. Whether she was out in public or at home, she was elegant in her dress and gracious and soft-spoken in her manner. She accentuated her beauty by highlighting her already flawless, porcelain skin with her favorite brand of makeup, Estee Lauder. Her favorite perfume was Ecusson, her favorite color blue, her favorite flower the rose. Friends and relatives who knew her best affirm that her tastes in fashion, furnishings, art, music, in civility itself, were traditional, classic, refined, and yet, without contradiction,down-to-earth. She embodied the Greek principles of order, elegance, and simplicity, all symbolized by her own favorite flower, the rose, the same flower Ken Piper sent daily in bouquets to Virginia during his courtship. It is not difficult to imagine how her tastes developed over the years, from the time when she was a young woman forced to conserve because of the Great Depression to the years of her marriage to Paul, who delighted in helping her widen and cultivate her tastes, and finally to her years with Ken, who encouraged Virginia to relax into her own life and give herself permission to revel in happiness.

Born in Beardstown, Illinois, on July 24, 1906, Kenneth Piper graduated from the University of California at Los Angeles in 1929 and Loyola University Law School in 1936. He served as an FBI special agent for seven years as one of the original G-men before resigning to join Bausch & Lomb Optical Company, where he worked for five years as director of industrial relations. In 1949, Paul and Bob Galvin hired Ken away from Bausch & Lomb to become vice president of human relations for Motorola, Inc., a position he retained until his retirement in 1973. In 1971, he was appointed special assistant to the chairman of the board. Bob Galvin offers the following description of Ken:

He was a very capable leader. Ken Piper was one of the few people in our company I personally hired. I hired him because I was looking for someone who was a sales manager in charge of our personnel department, who could stand strong if there was ever another attack on the company becoming unionized. Ken was a very tough fighter. He was good, strong, and honorable.

In 1952, at the age of forty-five, Ken married for the first time. He and Dorothy Isabell had no children, and in 1968, nine years after Virginia had lost Paul to leukemia, Ken lost his wife.

A longtime friend of Paul Galvin’s, Ken had worked for Motorola, Inc., for twenty years, so he and Virginia had known each other on a casual professional basis for the same amount of time. One recollection of how Ken and Virginia became better acquainted is offered by Christine Ekman, wife of the late commercial and fine artist Stan Ekman:

Ken was a very confident, very nice person. You knew he was in the room; he commanded attention. When Virginia ran into Ken at a Motorola meeting, he offered to drive her from Phoenix to another Motorola function they were both attending in Tucson. She accepted, so on that two hour ride down and back, they had a chance to get better acquainted. Stan and I had been friends of Ken and his first wife Dorothy, so one day Ken called us and invited us to dinner, saying, "I'd like you to meet a new friend of mine." Well, of course it was Virginia, and we already knew of her from her time as Paul Galvin's wife. After they were married, the four of us started going out together. We traveled together and had a lot in common. Early in their marriage, the four of us traveled to California and stayed in Laguna Beach. We rented an apartment and went to Disneyland, a place Virginia had always wanted to see. As Mrs. Paul Galvin, everything had always been very formal, she couldn't let loose, so she had such a wonderful time on that trip to Disneyland, doing things she couldn't normally have done as Mrs. Paul Galvin. Nobody knew her there. It was really good for her. She just loved the opportunity to relax.

Going to Disneyland with friends who moved in artistic, less conformist circles and being with Ken gave Virginia the opportunity to unleash more spontaneous, ebullient parts of her nature. It must have been a marvelous breath of fresh air; one imagines Virginia, Ken by her side, on rides at Disneyland, whirling giddily about, laughing, letting go of her image as a figurehead of respectability and dignity and becoming, with Ken’s encouragement, momentarily carefree, as blithe-spirited as a girl.

Longtime friend Sister Ann Ida Gannon offers another perspective of Virginia during the years of her marriage to Ken Piper. Appointed in 1957 as president and superior of Mundelein College, Sister Ann Ida courageously led the college through some of the most progressive, innovative changes within the Catholic Church, an era beginning in 1962 with Pope John XXIII (1958-1963) and the Second Ecumenical Vatican Council, or Vatican II, followed by Pope Paul VI (1963-1978), Pope John Paul I (1978), and Pope John Paul II (1978-2005).

By 1950, Mundelein College was the largest Catholic college for women in the United States, and Sister Ann Ida Gannon distinguished her own term as president and superior by founding an intellectually vigorous religious education program, inviting theologians worldwide to lecture, and by encouraging active involvement in the civil rights, feminist, and antiwar movements, all of which set a liberal academic tone for the campus.

This young, remarkably progressive religious leader first met Virginia over the telephone in 1964. Sister Ann Ida remembers immediately “hitting it off” with Virginia, even in that first phone conversation, and theirs became a thirty-five-year friendship based initially on Virginia’s philanthropic gifts to Mundelein and then evolving into a deep friendship between two intelligent women of faith who demonstrated equally powerful leadership and humility in their intersecting fields of work. Sister Ann Ida remembers the following:

Virginia talked a great deal about her grandmother, whom she loved very much. She also told me the story of how her husband Paul’s deep faith had influenced her decision to convert. I marveled that Virginia, and this was particularly true of her time in Phoenix, kept tabs on the gardener, all the various workers she’d had in Chicago: these were the important people in her life. Virginia was very busy and had a few close friends, but I think so many of her friends were friends she was doing something for, so one of my aims was to be a person who could do something for her.

There was an absolutely beautiful simplicity to Virginia. Her gardener, her maids, the people who worked for her, they all sat together at one table. She had a very genuine love for them. She had no airs and was surprised by the amount of Paul Galvin’s fortune.

As a college president, I tried to raise a lot of money, and I’ve dealt with extraordinary types of people from all over the country as well as on various boards, and usually, people have several sides to them. For some, it’s very important to be famous, to name-drop, to let you know that they know this or that person or that they saw the President of the United States. This was never part of Virginia’s conversation. I wouldn’t have known what in the world she’d done. In fact, when I did her records at one point, I was amazed at the extent of her charities. She was utterly unpretentious, a simple person who became a multimillionaire. Nevertheless, she was sophisticated enough to know that you have to fulfill the role you’ve been given, though she was never fooled by people’s fawning or false praise.

At the beginning of their marriage, Virginia and Ken lived in his modern condominium overlooking Lake Michigan at 1630 Sheridan Road in Wilmette.

In 1972, the year Ken and Virginia moved to Arizona, housekeeper Alma Althoff retired and moved to the Georgian, a beautiful retirement residence in downtown Evanston, her expenses fully paid by Virginia. Following Alma, Sister Mary Cyril Tirpak would become a source of loyal support and friendship to Ken and Virginia.

When Sister Mary Cyril began experiencing severe headaches, preventing her from teaching literature and music, the mother superior of the order asked if Sister Mary would be willing to care for an elderly couple, Ken and Jessica Critchfield, in their home in Oak Park, Illinois.

Gentle and kind, Sister Mary cared for Ken Critchfield until his death on January 16, 1972, at Scottsdale Memorial Hospital; she also cared for Jessica until her death on August 21, 1972, at Ken Piper’s home on Sheridan Road in Wilmette. Jessica had been living at Ken’s house with full-time care, and Virginia, Ken, Carol, and Sister Mary were all by Jessica’s side when she died. Virginia’s parents are entombed at Greenwood Memorial Cemetery in Phoenix.

Eventually, Virginia invited Sister Mary to live with her permanently. With Sister Mary in the official capacity of housekeeper, companion, and cook, their relationship over eighteen years assumed a rich dimension of friendship and mutual devotion. As Sister Ann Ida Gannon, who knew both women well, put it, “Sister was a very simple, beautiful person. Virginia had a great love and appreciation for her. Sister Mary was from a humble background; she was loving and dedicated. The two of them would sit there at the kitchen table, working together, just like sisters.”

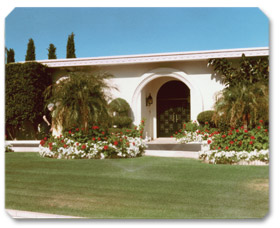

Soon after her parents’ deaths, Virginia and Ken made a permanent move to Arizona in November 1972, purchasing a home under construction in Paradise Valley and having it custom-finished according to their specifications. While their new home was being completed, the Pipers lived in a home Virginia had bought in Mountain Shadows at 5635 East Lincoln Drive. With Motorola gaining such a significant industrial presence in the Valley, Bob Galvin and his family had also built a second home at the nearby John Gardiner’s Tennis Ranch, and in 1973 Carol Critchfield purchased Virginia’s home in Mountain Shadows and made a permanent move from Riverside to Paradise Valley.

After his marriage to Virginia, Ken’s position at Motorola changed. Bob Galvin, still chairman of the board of Motorola, named Ken assistant to the chairman of the board, charging him with reducing employee healthcare costs. Motorola, at that point, was the largest employer in the Valley, and to help reduce the massive cost of employee healthcare, Bob needed Ken to put together a task force of attorneys, physicians, and businessmen who could make fair but cost-efficient healthcare recommendations that would benefit Motorola employees.

Virginia and Ken finally moved into their new home on 7818 North Arroyo Drive in Paradise Valley in 1973. Large but not ostentatious, the Pipers’ home had four bedrooms, a kitchen, living room, dining room, atrium, and separate offices for Ken and Virginia. The backyard swimming pool was encircled by lush beds of roses, planted perhaps in lasting tribute to Ken’s courtship of Virginia. The grounds were immaculately maintained, always freshly planted with geraniums and other bright seasonal flowers. Virginia had persuaded her gardener in Evanston, Dick Nowack, and his wife, Del, to relocate to Arizona and continue to work for her, which he did until Dick’s death in the mid-1980s.

The Pipers’ new home in Paradise Valley was Mediterranean-style, serene, and elegant, reflecting Virginia’s need for harmony, order, and beauty. In a letter to Charlene Piper, a relative of Ken’s, dated June 25, 1978, Virginia described their happy life during this time.

Ken was an outstanding man, handsome, vital, intelligent, warm, gracious, witty, and wonderful. Our home, located in an area enchantingly called Paradise Valley, was brand-new, bright and cheery, and really custom made for us. We had scores of friends, his, mine, and ours, many through our Motorola affiliation, and soon we had many more. We became involved in numerous projects, traveled a good bit, entertained frequently. Ken, a born crusader, participated in numbers of local causes, medical and rising costs, for one. He was on numerous boards and served as chairman of the board of directors for the Arizona Heart Institute.

Christina Critchfield-Huber, Paul Critchfield’s daughter by his first wife, Susie, and sister to Kendell Critchfied, remembers Ken Piper with great fondness:

I first knew Ken when I was four years old. It was Christmastime, and I remember Virginia pretending she was Mrs. Claus, saying, "Oh, let's call Santa Claus before he comes, let's give a special message to Santa Claus!" I was so excited! Meanwhile, Ken would be in the next room, waiting to appear as Santa Claus. Ken was the most awesome man. There are such strong women in my family, Virginia and my grandmother, Mimi. And Ken was really like, well, "the softer side of Sears." They were an awesome team. You knew you could just hug the guy, and he and Virginia just really enjoyed and loved one another so much.

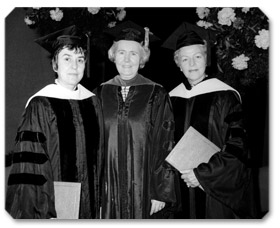

During the brief time Ken and Virginia lived together in Arizona, Virginia served on advisory boards for the bishop of Phoenix, the Franciscan Renewal Center, and the Scottsdale Girls Club. Back in Chicago, projects funded by the Paul V. Galvin Charitable Trust continued, and in June 1973, Virginia was presented with an honorary degree from DePaul University. A particularly meaningful tribute to Virginia occurred June 8, 1974, at Mundelein College’s forty-third annual commencement exercise. With Ken and other invited guests present to share in her honor, Virginia, as a former Chicagoan and administrator of the Paul V. Galvin Charitable Trust, was awarded the honorary degree Doctor of Humane Letters for her role in providing the Paul V. Galvin Memorial Hall and establishing the Galvin Scholars Program and for her years of devotion to Mundelein College. In tribute to Virginia, Daniel G. Cahill, vice president of development, read the following citation during the commencement:

Her rapport with young people and her desire to become more personally involved in the needs of the younger generation influenced her decision to distribute the assets of the charitable trust established by her late husband, Paul V. Galvin, to Mundelein, Notre Dame, Loyola, DePaul, Northwestern, and other midwestern educational institutions. Saint Francis Hospital, Evanston, and Saint Joseph Hospital in Chicago received substantial shares of the estate as evidence of her regard for the health needs of Chicagoans. Typically, her role in these and countless other generosities is usually anonymous. The memorials established in Mr. Galvin's name reflect not only his concern for the young and the ailing but also Virginia G. Piper's determination that his dreams be fulfilled. Her concern does not stop with the dedication of a building or the implementation of a program. The progress of Galvin Scholars at Mundelein, for example, and their achievements after graduation are followed avidly by Mrs. Piper, who writes of her "vicarious involvement in the careers of our Mundelein daughters."

From her spacious, light-filled home office, Virginia continued to conduct a massive volume of personal and business correspondence, the former handwritten on cards or her custom-made blue-bordered stationery, the latter typed on the old manual Royal typewriter that she used to the end of her days, refusing all offers of electric typewriters, word processors, or computers. Every bit of correspondence that made its way off Virginia’s enormous desk was from her own hand, a phenomenal feat indicating the heart and sincerity she placed in her relationships with people, whether by taking the extra time to write a warm personal note or hand-typing a more formal business reply. Here, for example, is an excerpt from a personal letter of Virginia’s written to Sister Elaine Cabellier, administrator of Marillac College in St. Louis, on April 16, 1974:

Dear Sister Elaine:

Thank you very much for your letter, referring so affectionately to Sister Bertrande, who was, as perhaps you know, very, very special to me, too. During 1948, when I was taking my instructions in Catholicism, I had the wonderful privilege of visiting with her on many private sessions of added "instructions." How I loved those visits and looked forward to them. We would go upstairs to a small guest bedroom at Marillac House and talk about God for one or two hours. She was never too busy for those wonderful talks. I know very well what you mean when you say you loved her dearly and learned much from her spiritually. Sister Bertrande was a very special person. By example she influenced many others to do and give their best to draw from themselves more than they had imagined existed within.

Both Ken and Virginia loved to entertain, to host parties and charity events, the most remarkable of which was the dedication of the Paul V. Galvin Life Science Center at Notre Dame University in 1972. Loading a hired bus with some forty specially invited guests, Virginia had the entire group driven to Notre Dame from Chicago. All the guests attended an impressive banquet, where Virginia, in inimitable fashion, surprised the university and its president, Father Hesburgh, by presenting another check for $250,000 to purchase equipment for the Science Center. The entire day-long event was a superbly orchestrated, fabulously fun occasion, and on the bus ride back to Chicago, Ken fixed his famous Bloody Marys for everyone. The dedication was a celebration those who were fortunate enough to attend would remember and talk fondly about for years. Severene Orth, longtime friend of Virginia and Ken’s, and her husband Ray, a Motorola employee for thirty-six years (the last twenty-two as administrative assistant to Ken), were two of those guests.

In remembering Virginia, Severene said:

Ken idolized her. He was a mentor to my husband, Ray, so Ray felt about Ken like I did about Virginia. They were very special people, and you would do anything for them. She had something beyond charisma. You just knew this was an individual God put on this earth for a very certain reason. You know the phrase "Angels among us"? She was a tremendous inspiration.

On May 19, 1972, not long after that gala dedication of the Life Science Center at Notre Dame University, Virginia responded to a letter from her twenty-six-year-old nephew, Paul:

Dearest Paul,

Your beautifully worded letter, remarking so sensitively on Dedication Day at Notre Dame, reached me today. No comment I have received on that wonderful day meant quite as much. You do understand what all of this means to me and why. I am totally assured when I read your words: "As we've said before, it is great joy to share in the good things that are being accomplished in our day, to push aside the Vietnam War, the civil disturbances of our cities. When I share with you in these good things, I feel greatly lifted and inspired. All of us who shared in the Dedication of the Life Science Center were spiritually renewed." This is all a part of the privilege it is to have the stewardship of charitable funds, the unparalleled joy of giving toward the betterment of mankind. It does, indeed, quicken my heart to reflect upon the miracles, the wonderful mysteries which may be solved in our Life Science Center, an awesome thought. You and I must talk together about the projects more objectively and about the joy of giving. It is a big responsibility if it is to be conducted with judgment and heart. You can have the former with exposure and experience; you have the latter in abundance now. Thanks, my dear, for sharing my ideals, my goals, and particularly for understanding the basic motivation. Don't ever compromise your high ideals. You need not; you must not. You are, it seems, the one to assume eventual responsibility. Please know how much your letter means to me, as do you.

Devotedly, Gin

During the late afternoon of January 21, 1975, Ken came into the house from working in the garden, a favorite activity, and began to prepare his and Virginia’s customary cocktails. Standing at the kitchen sink, with her back turned to him, Virginia listened as her husband related an amusing incident from the day’s business luncheon. The phone rang, and Ken answered but then suddenly fell silent. Virginia turned to find him slumped in a chair beside the phone, his face constricted. He was having trouble breathing. Less than two minutes later, Ken Piper, a vibrant man of sixty-four, who had received a clean bill of health from his doctor earlier that day, was dead. The shock to Virginia was devastating.

Months later, in a letter to Sister Carol Frances of Mundelein College dated April 9, 1975, Virginia would try to describe her loss.

Dear Sister Carol Frances:

Please excuse my long-delayed reply to your lovely letter of November 25. As you probably know, I have just lost my husband, Ken, and I move through the days following with the numbness and detachment of a sleepwalker. He died very, very suddenly (in about two minutes), laughing and talking with me one moment, the next slumped in a chair, breathing with great difficulty, and then gone.

Despite every resolve, every effort, I find adjustment and acceptance extremely difficult. Our life came together magically just five years ago (a second marriage for both), and somehow we dared to believe that we were to have quite a few more years of our special happiness, a kind of "reward" for earlier sorrow in each of our lives. Not so. And this is the imponderable. With absolutely everything going for us, this sudden loss is suffocating. I do thank God for the fact that he did not suffer an incapacitating and long-drawn-out illness. He was a vigorous, energetic, courageous, outgoing, warmhearted man who loved life and people and gave generously of his time and talents. Please keep me in your prayers, if that is not too much to ask. I have a l-o-n-g way to go, I fear, before I find inner peace and before I can accept the death, so untimely, of such a wonderful man.

In the hours and days and weeks following Ken’s death, friends, family, and clergy surrounded Virginia. A viewing service was held at Messinger Chapel in Scottsdale, followed by a funeral Mass on January 25 at Our Lady of Perpetual Help Church, officiated by Father Michael Weishaar, the same priest and close friend who had married Ken and Virginia. Ken was entombed beside Virginia’s parents at Greenwood Memorial Cemetery in Phoenix, and because his presence in Illinois had also been significant, an additional memorial Mass, presided over by Monsignor Fitzgerald, was held at Ken and Virginia’s former church, St. Athanasius, in Evanston. A recording of that service was sent to Virginia by the Hubata family. Sister Ann Ida Gannon flew out from Chicago within a few days of Ken’s death, staying by Virginia’s side for ten days, helping her cope with her devastating grief. Sister Ann Ida recalls Virginia saying, in calmer moments, that she was thankful at least that Ken hadn’t suffered. No doubt she was recalling the slow, agonizing death of her first husband, comparing it to the opposite shock of Ken’s death without warning in the midst of normal routine. Perhaps she was asking herself why two husbands, marvelous men she had cherished and loved, had both been taken from her.

Kenneth Piper’s elegance, charm, and integrity had matched Virginia’s perfectly, and they had enjoyed five years together,five years and twenty-two days, in Virginia’s words, “a precious, beautiful, unforgettable CHAPTER” in her life,and once again, Virginia, now sixty-three years old, found herself widowed and alone. Although she would live another twenty-four years, longer than the combined span of both marriages, Virginia would not marry again. “I’ve had two of the most fabulous husbands,” she would often say. “And I know that kind of luck could never happen again.” And just as she had stayed on in the house on Normandy Place after Paul died, Virginia remained in the house on North Arroyo Drive, though for years she never entered Ken’s office, never touched his things, preferring to leave them just as he had. Another person might have chosen to sell the home, attempt a fresh start in new surroundings free of memories. But Virginia, temperamentally averse to change and perhaps out of tribute to the house she and Ken had helped design and lived in for so brief a time, chose to stay, to carry on in the best way she knew how, surrounded by friends, family, and the challenges and rewards of philanthropic work. The world was always needy, the poor always there. Virginia, with no husband or children of her own, would gradually discover that she had a specific purpose, perhaps even a destiny, to fulfill. Living in service to others, being “unselfed,” as her grandmother might have described it, would eventually over a long and uneasy time become her chosen response, her anchoring grace.

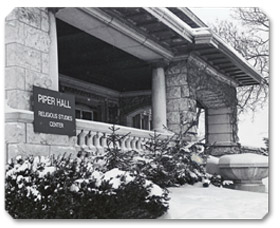

Eight months after Ken’s death, one of the first public events Virginia managed to participate in was the dedication of the Kenneth M. Piper Hall, Center for the Study of Religious Education, on September 21, 1975, at Mundelein College. The dedication, planned before Ken’s death, now held for Virginia an added and anguishing poignancy. After the Mass, celebrated by Monsignor Fitzgerald, a tearful Virginia gave the following remarks at a buffet luncheon:

I am sure you all know that today is a day of mingled emotion for me. It's a day of great pride and gratitude to think that a beautiful building like this could be dedicated to Ken. And it's a day of joy that I can share it with so many of our friends. And it is a day of inevitable recall for the day that Sister mentioned, when Ken was here with us, less than a year ago. I have so much for which to be grateful today, and I think the thing for which I am most grateful, and I am sure you will understand, is that I have found it very difficult to accept and to adjust to losing Ken really so soon after our life had started out so beautifully. But I do know that after today and during today and because of today, thanks to all of you, Father, Sister Ann Ida, and all the Sisters, I give thanks for the very spiritual strength the day has brought to me, and I'm sure to all of you, that I have reached a point now where I can go on.

Following Virginia’s remarks, Sister Ann Ida, obviously moved, responded simply, “I think that all I’d really like to say, Virginia, is that your faith strengthens our faith.” As president of Mundelein College, Sister Ann Ida continued to be a close personal friend of Virginia’s as well as a philanthropic associate. It had been during the dedication of the Paul V. Galvin Resource Learning Center at Mundelein College in 1969 that Virginia had quietly confided to Sister Ann Ida the news of her engagement to Ken Piper. Now, the two women stood together dedicating the Center for the Study of Religious Education in Ken Piper’s memory, two friends, both of high public profile and steadfast spiritual faith, in loyal affection for each other, an affection that would last until Virginia’s death in 1999.

The year of Ken’s death also saw Virginia present at the dedication of the Paul V. Galvin Heart Pavilion at Saint Francis Hospital in Evanston. It speaks to Virginia’s character that even while newly bereaved, she would continue her good works on behalf of her first husband while continuing to honor her second husband. During that dedication, the hymn “You are Near,” as sung by the St. Louis Jesuits, must have offered Virginia momentary solace and shone light on the seemingly bleak path before her.

Lord, you have searched my heart,

and you know when I sit and when I stand.

Your hand is upon me protecting me from death,

keeping me from harm.

Where can I run from your love?

If I climb to the heavens you are there;

if I fly to the sunrise or sail beyond the sea,

still I'd find you there.

You know my heart and its ways,

you who formed me before I was born,

in the secret of darkness before I saw the sun

in my mother's womb.

Marvelous to me are your works;

how profound are your thoughts, my Lord.

Even if I could count them, they number as the stars,

you would still be there.

You Are Near, 1971, 1974, music & lyrics by Daniel L. Schutte

Bittersweet solace would no doubt come, too, from memories and mementoes, physical touchstones of cherished times with Ken, the sort of plain, simple things Virginia treasured, things heartfelt and natural, like their private word “foreverly,” their favorite song, “Embraceable You,” and the numerous handwritten notes from Ken, found carefully saved among Virginia’s papers at her death.