The Philanthropic Journey Begins (1959-1969)

Memories

Kerry Hubata, daughter of Joe and Nell Hubata, fondly remembers the great sense of fun her mother and Virginia shared whenever they were together, “cutting up,” “clowning around,” and generally acting like twelve-year-old girls. Of the many times she and her parents were dinner guests of Virginia’s at Westmoreland Country Club in Wilmette, Illinois, Kerry recalls one in particular. There was a long hallway in the club carpeted in a geometric pattern, and as Kerry and her father watched, Nell and Virginia, giggling like schoolgirls, hopscotched all the way down the length of that stately hall, repeating the words hop, hop, jump, hop hop, jump. “That’s how I remember Virginia with my mother,” Kerry said.

Hello, Ginny:

This is Saturday evening, February 8, 6:00 p.m. Mother and I have just had dinner, and tonight we had our usual Saturday evening cheese on toast. It was very nice, and the way Mother makes this, it’s just marvelous. This is one of the dishes we used to have every Saturday evening when we lived in St. Louis, before we went to the Grenada in the old vaudeville days and later on when we went to the Missouri and saw Brook Johns. I’ll never forget those days. We always had so much fun, and we’d typically end the evening by going to the Bluebird for one of their delicious sodas. The one that we usually had was a big gob of ice cream with almonds on it. I forget what they called that dish, but that was what we used to have. Then we’d get a newspaper and go home, where you girls would read the funnies, and we’d pick up on the news and finally get to bed somewhere around midnight. Virginia, you deserve a lot of credit for handling all these people who are pestering you for money. We can’t thank you and Carol enough for the tapes you are sending. And we say over and over what dear, devoted daughters we have and how grateful we are. We’re coming to the end of the tape now, here we go, bye-bye!

from an audiotape sent to Virginia from her parents, February 8, 1964

Valley Ho Resort, Scottsdale

During the last year of Paul Galvin’s life, the momentum of world events swept on.

Charles de Gaulle became the new French president, Fidel Castro took over Cuba, Jawaharlal Nehru was prime minister of India, and the Dalai Lama escaped from Communist Chinese forces entering Tibet. In America, Hawaii became the fiftieth state, hula hoops enjoyed a brief rage, and rock-and-roll continued to become a national musical phenomenon. Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The Sound of Music opened on Broadway, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum opened in New York City, and on American television, 77 Sunset Strip, Gunsmoke, Bonanza, and The Lawrence Welk Show were some of the nation’s most popular programs. The ’50s had been a decade of optimism and prosperity, with the domesticity of wives and mothers glorified even as more women than ever entered the workforce.

Against this international and national backdrop, Virginia, now a forty-eight-year- old widow, embarked on a new and solitary chapter of life, assuming duties and responsibilities, roles of leadership, and influence she had never experienced before. She inherited half of Paul’s estate; the other half went to the Galvin family. For the next ten years, Virginia continued to live in her home at 3038 Normandy Place, where she had lived with Paul. Alma Althoff, her housekeeper and increasingly cherished friend, continued to live with Virginia as well. These were challenging, lonely years, relieved by family, friends, and the welcome distraction of musical and theatrical events, golf games, charity balls, fundraising events, and business meetings. Virginia’s stepson, Bob Galvin, had become president of Motorola Corporation, and Mary, the new “president’s wife,” now filled the prestigious role that had once belonged to Virginia.

Virginia’s portrait

At the time of Paul’s death, Virginia had been on excellent terms with the Galvin family. She remained devotedly close to her parents, sister, and teenage nephew, who were still living in Riverside, and maintained the friends she had shared with her husband, couples such as the Vincent Sills, Philip and B. J. Sheridan, and many others. But to have become the new widow of such a prominent and legendary figure as Paul Galvin could not have been an easy or swift adjustment.

After Paul’s death, Virginia experienced an abrupt if subtle decline in social stature as her charitable responsibilities increased and her public profile receded. Virginia’s life at this time was atypical. In a postwar era that glorified women as wives and mothers who ruled increasingly prosperous homes in the suburbs, Virginia had neither a husband nor children. What she had was her husband’s wealth and her promise to complete his philanthropic projects, to honor his legacy. How to do that was the challenge she faced, but it was a challenge that became a comfort-as her strongest tie to Paul, and a test of character.

Just as hard work had been a source of emotional recovery and resilience in the Galvin family, Virginia, following her late husband’s model, drew upon a natural discipline and native conscientiousness, coping with loneliness through work. Meeting regularly with Paul’s bankers, stockbrokers, and financial advisors, principally with Hugh Solvsberg, at the Harris Trust Bank, she undertook the task of learning everything she could about the world of finance, investments, tax laws, and trust and estate accounts. Combining resolve with an innate dedication to detail, Virginia would become, under the tutelage of her trusted advisors, as astute and shrewd as any man of her era in the labyrinthine world of high finance, investment, and philanthropy. Virginia made it her business to be unintimidated, and the most honest way to do that was to learn exactly how the principles of business and finance operated.

She would not be known as the woman who had married well, and blithely signed checks for various causes; Virginia intently examined each project, charted its progress, gauged its leadership trajectory, and attended related functions. Her gifts, large and small, public and private, from the earliest years were accompanied by high standards, firm expectations, and an eye toward longevity and integrity of mission.

Doubtless, Virginia forged a new path of power and philanthropy unknown to most women of her era. Characteristically, philanthropy was considered men’s work with their wives’ names attached (if at all) to both major and minor gifts. Virginia initiated a journey that would prove remarkable in philanthropic scale and scope, unique (though initially unheralded) in American women’s history and charitable giving. Was Virginia aware of how her life course would forge a new historical path-both in terms of philanthropy and women’s stewardship? Perhaps. Virginia, however, was unmotivated by worldly pride or concern for social stature. The origins of her new journey were rooted in her own character, in her love for Paul Galvin and for humanity, and always in the abiding need to live “a dedicated life.” Dedication for Virginia meant a tireless work ethic, visionary leadership, and a grounded understanding of the financial and social impact of her gifts.

One of Virginia’s first charitable endeavors, among the hundreds that would compose her career, was to underwrite and see to fruition the Paul V. Galvin Coronary Care Center (CCC) at Saint Francis Hospital in Evanston. A subsidiary of the Paul V. Galvin Heart Center, the CCC would provide a complete program of cardiac care and put Saint Francis Hospital at the forefront of cardiac medicine in the state of Illinois, eventually earning it the name “The Heart Hospital.” Saint Francis was the facility where Paul had died, so it seemed appropriate that Virginia’s first major grant as chief administrator of the Paul V. Galvin Charitable Trust would be awarded to the hospital whose doctors, nurses, and staff had cared for him so skillfully and compassionately. Dr. Philip Sheridan, Paul’s attending physician during his final illness, recounts the first stage of this early gift of Virginia’s:

Paul V. Galvin Coronary Care Unit

One day, after Paul had died, I got a call from Virginia, and she said, “Phil, I would like to visit with you because I have a program I’ve become interested in, and I want to know if you think I should underwrite it.” I went over and visited her the next day, and she told me about the program, which I thought had a lot of merit, though it wasn’t in my field; it was in the field of social science.

At that time, I was the overseer of a project at Saint Francis Hospital that Bob Galvin and his father, Paul, had underwritten, the foundation of the first heart center in Cook County in 1957. This was back when open-heart surgery was just being developed, and there was a lot of promise on the horizon because the chest surgeons had successfully taken on congenital heart defects in children, showing that, yes, we could operate on the heart. Before that, the surgeons had been afraid to even touch the heart. So an allied program had been developing in addition to an awakening concept in medicine that the quality of care for people having heart attacks could be improved with early treatment. It had been demonstrated at a couple of university hospitals that the mortality rate of people arriving at the hospital with heart attacks could be cut by 50 percent if they had a coronary care center with proper equipment. Our cardiologists were anxious to get that going, as they were already successful in doing cardiac catheterization work in the new heart center that Paul and Bob had underwritten.

So I visited that day with Virginia and said, “I think your project is very nice, but I have another idea you may be interested in, one that I guarantee you will save many lives.” She replied, “What’s that?” So I described the concept of the coronary care center, and Virginia said, “I think I’ll go with that instead. How much money do you think it will cost?” I told her I didn’t know, that perhaps a quarter of a million dollars would handle it. As it turned out, it was closer to half a million, but she didn’t object.

That Paul V. Galvin Coronary Care Unit is still in full operation today, and it’s saved thousands of lives. Virginia was present at the dedication, and John Patrick Cardinal Cody, bishop of Chicago at the time, dedicated the center. It is a magnificent tribute to her benefaction. She was so very gracious about it, including increased costs we hadn’t anticipated. The CCC is still, today, an invaluable adjunct to the Paul V. Galvin Heart Center.

It is often the smallest moments that mark great turning points in a life, and the moment Virginia decided to commit funds to the heart center after initially consulting Philip Sheridan on another project-the moment she made her first independent decision about which cause to support-may have been the one that ushered in a new awareness of her power, her extraordinary ability to affect lives on a grand scale, and the understanding that ultimately the choices she made would be hers alone.

Taking sole administrative leadership of the Paul V. Galvin Charitable Trust, Virginia carried out numerous projects reflecting Paul’s charitable interests, many of them in medicine and education. Among these were the following: the Catholic Chapel at the Stritch Medical Center in Maywood, Illinois; the Paul V. Galvin Memorial Chapel at the Loyola University Medical Center; the Geriatric Department at Saint Joseph Hospital in Chicago; the Paul V. Galvin Life Science Center at Notre Dame University; the Paul V. Galvin Coronary Care Center at Saint Francis Hospital in Evanston; the Speech Therapy Department at Chicago’s Rehabilitation Institute; the Paul V. Galvin Memorial Chapel at Northwestern University; the Fine Arts and Communications Center at St. Ambrose College, Davenport, Iowa; the Paul V. Galvin Resource Learning Center at Mundelein College, Chicago; and extensive scholarship programs at DePaul University; Mundelein College; Holy Cross Seminary; the College of Saint Teresa, Winona, Minnesota; Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College, Indiana; Moreau Seminary, Indiana; and the National College of Education, Evanston, Illinois.

The early paradox Virginia witnessed between her grandfather, a medical doctor, and her grandmother, a Christian Science practitioner who declared disease a mere error in thought—and the equanimity they shared-was mirrored in her tremendous support of medical institutions and medical research while quietly adhering to her grandmother’s spiritual tenets. She was able, as well, to reconcile Christian Science with Catholicism or to allow them to at least coexist peaceably within her belief system.

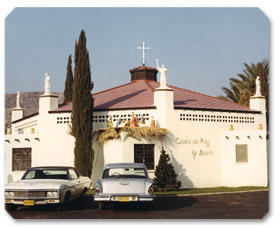

In 1967, Virginia also funded the expansion and renovation of the Paul V. Galvin Chapel at the Franciscan Renewal Center, also called “the Casa,” founded by the Franciscan Friars as a spiritual retreat center. The FRC, or Casa de Paz y Bien (House of Peace and Every Good), remains a Spanish-style desert oasis in Paradise Valley, Arizona, set between two Phoenix landmarks, Camelback and Mummy Mountains.

In other charitable capacities, Virginia accepted many invitations to serve in leadership roles among several organizations: she served as a member of the first advisory board of Marillac House in Chicago and as a member of the One Hundred Club of Chicago, an organization furnishing aid to the widows of policemen and firemen; she also served on the boards of DePaul University, Northwestern University Settlement, the North Shore unit of the American Cancer Society, the Cradle Society, and Saint Francis Hospital in Evanston.

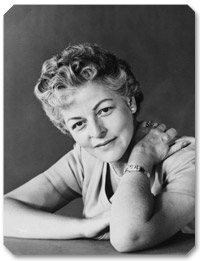

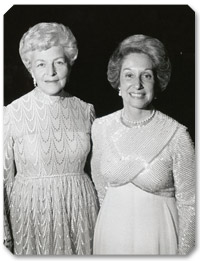

Such lists, while extensive and impressive, cannot begin to convey either the vast human scope of her philanthropy or the many and constant demands upon her time and energy. To offset some of the relentless desk work, phone calls, letters, meetings, and site visits, all of which she assumed sole responsibility for, Virginia found respite in the practice of her Catholic faith and in her family and friends. Two new friendships, both initiated in 1964, would prove especially enjoyable to Virginia. At some point that year, Virginia was introduced through Les Muter, a businessman she went out with, to Dr. Joe Hubata, his wife Nell, and their nineteen-year-old daughter, Kerry (then a ballet dancer, now director of the Evanston School of Ballet). According to Kerry, Nell and Virginia “hit it off instantly.”

They became inseparable, like sisters. Virginia would come to our house to visit, and we didn’t come from a lot of money—we lived on the south side of Chicago near 104th and Rose-but what my mother offered Virginia was honesty. When you’re the king or the president, no one’s going to tell you that you don’t have any clothes on! Mother also had an impeccable sense of style, and she would go shopping with Virginia. The two of them devised a whole set of hand signals to use in the dressing room. The salesperson who had latched onto Virginia would bring in a whole bunch of stuff, the most expensive stuff possible, trying to make a sale, and sometimes they didn’t look that proper, and so Mother would give Virginia these little hand signals. They had it down pat.

Kerry also fondly emphasizes Virginia’s great sense of fun:

She was clumsy, always dropping food and spilling things, and one of Mom’s favorite things to do was to go to Neiman Marcus and have popovers and coffee. So we were all there one time, when Virginia ordered a fruit salad and managed to spill something. All she had to do was look over at my mother, and without a word, they started laughing. Another time, Virginia was in one of her elegant formal gowns, all dressed to go somewhere, when she managed to spill something on her gown. You know what she said? “Oh, I don’t deserve nice clothes!” This beautiful, beautiful woman, who always put others at ease-who along with my mother used to talk with her hands, knocking over champagne glasses-could always poke fun at herself. And you know how teenagers will try on the same dress? My mother and Virginia would do that all the time, trying on clothes, visiting at one another’s houses, taking photographs: this is how I remember them.

Toward the end of 1964, Virginia formed a second close and enduring friendship with Laura Grafman, who is currently the executive vice president of the Scottsdale Healthcare Foundation. Laura recalls the day she first met Virginia in December of that year:

I was director of student financial aid at the National College of Education. The president of the college, K. Richard Johnson, called me to say Virginia Galvin was going to have lunch with him that day and talk about establishing a scholarship in Paul Galvin’s name. “Since you administer the scholarship program and all the student financial aid, why don’t you join us?” he asked. So I went down to his office at the appointed time and in walked this perfectly stunning woman, gorgeous, regal, with the most wonderful smile, the most engaging personality and look in her eye, and I just thought, wow! We talked the entire afternoon at the Homestead Restaurant, and it was a wonderful afternoon because I think we each knew we were going to be important parts of one another’s lives.

Virginia beautifully endowed a scholarship in Paul Galvin’s name, then invited me to attend a charity luncheon for which she was the honorary chairman. It benefited The Cradle, a home and adoption center for unwed mothers in Evanston. We met in December; the luncheon was in February. Our friendship started from there. We stayed in touch by phone and by mail, and when she went out to Arizona, I’d hear from her frequently.

Our paths crossed over and over for a number of years, at first having to do with scholarship projects, then later as close friends. How to describe it? Who would ever expect that a meeting initiated by a business obligation would develop into a lifelong friendship with the kind of depth we shared over the years? There was a twenty-year difference in our ages, but it never mattered in our friendship. It was an opportunity meant to be. That’s how I felt about Virginia. I had no idea, that day, when I walked into the president’s office, how that moment in time was going to change my life.

Virginia’s friendship with Laura and later with Laura’s husband, Dayton Grafman, would continue to flourish, deepening even more in the years after Virginia moved to Arizona. In June 1976, the Grafmans relocated from Illinois to Arizona, and Laura would prove, over the next thirty-three years, to be an invaluable helpmate, confidante, companion, and devoted friend to Virginia.

These new friendships—in addition to her continued close relationships with her parents, sister, and nephew; the Galvin family; old friends of hers and Paul’s; her housekeeper, Alma; and her hairdresser, dear friend, and confidante, Gladys Heimbaugh (later Gladys Leach)—helped sustain Virginia through the demanding public role she had taken on, a job requiring long hours of behind-the-scenes work and formal attendance at countless social and charity engagements. These friendships, many of them with people from modest backgrounds similar to hers, gave Virginia a much-needed sense of comfort and familiarity, a grounding in trust. These were people she could be herself and relax with, people who didn’t want anything from her other than her friendship. They loved her for who she was, not for what she had or for what she represented or for any prestige that might be gained by being her friend. Her housekeeper, who lived with her and ate with her, was a dear friend; her hairdresser stayed over on weekends, and they would go out together. Virginia loved to go to the Hubata house and relax in the kitchen, which she also loved to do at the home of her friend, Laura Grafman. What a relief it must have been to decompress after playing the grande dame, the gracious, gorgeous Mrs. Paul Galvin, and to sit at Nell’s or Laura’s kitchen table and just be herself and be loved for that.

Gradually, Virginia began going out with carefully selected male companions, not seeking a full-blown relationship, as she still deeply missed Paul, but looking for a pleasant companion. As beautiful as Virginia was, she suffered no lack of suitable gentlemen willing to act as escort. A number of men from her social set were happy to have Virginia on their arm, whether it was Ray Harkrider, Jack Kemmer, Jim Donnelly, or others. They provided her with company for charity events, golf or dancing, theater and concerts. This kind of socializing helped balance the loss of Paul, offering welcome diversion from her charitable work. Virginia was learning to navigate the constant demands made upon her resources by many worthy people from many good causes and organizations, each hoping to win her financial favor. The pressure of judging which causes most deserved Paul’s financial investment, and later her own, created a burden of responsibility few people other than a handful of other extraordinarily wealthy philanthropists might fully understand.

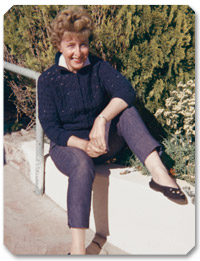

A few years after Paul’s death, Virginia began what she described as “tape-sponding,” making thirty- to forty-five-minute audiocassette tapes, “spoken letters,” and mailing them off to friends and family. Still extant is a partial collection of tapes made for her parents during 1963 and 1964, a few of the tapes co-recorded with her sister Carol or with an old friend from Tucson, a rancher named Jack Kemmer. The tapes record the surprising pleasure of Virginia’s gentle, musical voice. Not only do the tapes offer a gratifyingly intimate aural impression of Virginia’s personality, but they are also informative of an era. Virginia talks about the weather, how her yard looks, and what activities she planned for that day, all the small, almost humble details that revivify and contextualize her life. Rich vignettes emerge as Virginia humorously recounts her attempts to pack for an upcoming trip to Arizona; as she describes shopping expeditions and dress alterations at Blum’s or Martha Weathered, favorite Chicago stores; as she reiterates an emotionally charged, tearful determination to pick herself up out of her loneliness and live as Paul would want her to; or as she describes a concert or show to which she had treated herself.

What follows is a small sampling of excerpts from these audiotapes, which provide insights into Virginia’s daily life, both ordinary and extraordinary, as a widow on Normandy Place. Each of these tapes, addressed to her parents, begins very precisely: with the date, the hour, the setting, and a report of the weather. Invariably, Virginia signs off with a merry “Bye-bye, dears!”

This is one of those times I receive the strong feeling that Paul taps me on the shoulder and helps me with a situation; it’s a strange and wonderful thing.

February 4, 1963

I made eight tapes today! Tomorrow I will devote the entire day to tax work. I must keep my account book up to date, month by month, must record in my record book. The day will be quiet, lovely. I’ll peck along no matter how long it takes me. I’ve felt quite good today, and tonight Alma and I had dinner left from last night’s lovely dinner party. Here we go [reaching end of tape], bye-bye!

January 14, 1964

Such an honor to be Mrs. Paul Galvin. I must always conduct myself as a lady, as Paul would want me to be. It’s a simple code, really. I want to live that kind of a dedicated life. I had a strong feeling about that in church today. I was so glad to be back in church. I want to go every morning during Lent. Paul was the guiding light in all our lives; we should thank God that a saint like that is looking over us and continuing to guide us. I even ask him before I ask God and our Blessed Mother. I can’t imagine Paul’s equal ever coming into my life again, but with all my restless energy, I can’t just sink into a rocker.

February 1, 1964

In this new year, on my own, I will find that there isn’t a stigma to loneliness. [After going into downtown Chicago for business meetings, having lunch at the Chicago Athletic Club by herself, reading the Wall Street Journal, and finding she enjoyed the peace and tranquility of her solo luncheon.]

February 6, 1964

How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying—saw the musical in Chicago, loved it, could see it again. Dinner at the Blackhawk, show at the Schubert, would love to share with Carol and Paul. Discussed matter of Jack [Kemmer] on the way home with Ray [Harkrider], how I didn’t want to hurt Jack. I now know I can count on him [Ray] to be my escort this summer. With Jack, things only go up to a certain point, and though I don’t want to be emotionally involved with anybody right now, I don’t want to hang out with a bunch of widows either. I’m too proud for that!

February 10, 1964

It is difficult to capture the irresistible, evanescent appeal of tapes made when Virginia was in her early fifties, but there are hints of her need for tranquility, her reflective nature, an occasional weariness from the constant demands upon her, and a mystical reference to the occasional sense of Paul being close by, helping her. Virginia’s charm lay in her purity of heart. She was not unsophisticated, but she did possess a disingenuousness, a sweetness of nature. In the tapes, Virginia described to her parents rounds of social outings, parties, and dinners, most of which she seemed to revel in, perhaps as a relief from her work and responsibilities. Virginia adored the arts, and an evening’s dramatic or musical entertainment was a thrilling diversion from solitary evenings at home. Whether seeing Charade with Audrey Hepburn and Cary Grant or The Pink Panther with Peter Sellers or the San Francisco Ballet with Rudolf Nureyev and Margot Fonteyn; or underwriting and attending the annual Saint Francis Crusaders Ball with saxophonist Wayne King playing to a sell-out crowd of five hundred guests; or seeing current hit plays such as A Thousand Clowns or Under the Yum Yum Tree; or attending concerts featuring Mitch Miller, Andy Williams, or Fred Waring at the Arie Crown Theater or Abbe Lane and Xavier Cugat at the Palmer House; or sometimes simply watching Perry Como, Danny Kaye, Arthur Godfrey, or the latenight Johnny Carson on television; or listening to Torch Hour radio shows-as Virginia describes all of these, her enthusiasm and informed delight in the arts, in music, theater, and drama is evident.

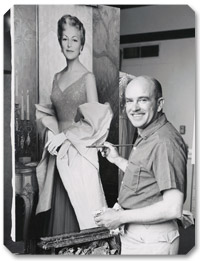

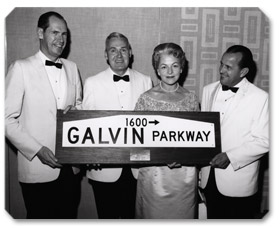

In the mid-’60s, Virginia flew out to Phoenix for the Galvin Parkway dedication, a significant media event attended by Mayor Milton Graham, Governor Samuel P. Goddard, Bob and Mary Galvin, Helen Galvin, and Burley Galvin. Around the same time, 1963 to 1964, Virginia commissioned a portrait from the immensely talented and well-known portrait artist Robert Harris. Virginia wrote about posing for her portrait at his studio in Scottsdale. The following is an excerpt from Virginia’s “Portrait Notes,” addressed as a letter to an unknown recipient and found among her papers after her death. The exceptional style and tone, the utterly self-deprecating charm, and the detailed admiration of another’s gifts are all distinctively and superbly Virginia’s.

This has been a busy year so far for me. I pulled up stakes on February 20 and flew to Scottsdale, weary to the point of exhaustion and, for the first time in my life, too close for comfort to pulling apart at the seams. I spent the first five days in Arizona just sitting quietly in the sun. Nothing is more remedial. When rest and solicitous friends and family performed their magic, I began to unwind. It was then that I launched myself into a new and fascinating project. I had my portrait painted. What could possibly better soothe a woman's ego than to have a talented artist portray her as a lovely, glamorous lady?

The artist, Robert G. Harris, formerly a successful magazine illustrator, having appeared between and on the covers of such leading publications as Saturday Evening Post, Ladies Home Journal, and Colliers, to mention a few, does not require the model to pose stiffly and self-consciously for hours. He has a pat and unswerving procedure. First come the "searching-for-the-pose" pencil sketches, made loosely on the large onion skin pad, thirty-two assorted drawings in my case. We studied these, laying them all out on the studio floor and eliminating the ones "unlikely to succeed." When we'd narrowed this selection down to three basic poses, he spent two hours taking countless pictures with all the photographer's special lights, lenses, etc. The first day we took fifty-three. From these we narrowed the pose down to a standing pose (the one pose I had sought to avoid lest I appear haughty-the "Grand Dame" kind of thing). But when I saw this particular pose alongside two other rather good ones, I suddenly knew it was THE one. He did not state his preference until I expressed my own. Then and only then did he say, "Oh, I was so hoping that would be your choice, Virginia, because, believe me, we can make this one terrific "really dramatic" socko!"

This was music to my ears.

The next day we devoted two hours to concentrating on the chosen pose—the correct turn of the body; the most complimentary tilt of the head; the arrangement of the hands; the softest, most flattering draping of the taffeta stole-which he felt essential to the drama and "upsweep" to the face the portrait must have. When we had finished on this day, he had taken sixty more pictures. In none of these was he satisfied with the position of my hands. One more day of photographing took place, 188 pictures in all!

On the last day I was in Arizona, I dropped into the studio again and sat quietly on an old bar stool about four feet from him while he worked painstakingly on the eyes, the nose, the mouth. The portrait, at this point, was mapped in a faint, incomplete way, with just the background and the hair and face, neck, and one shoulder finished. Curiously, impatiently, I called him from home one week later to see how it was coming along. He answered jubilantly, "I finished it today!"

Before shipping the portrait to me, Bob and his wife, Marge, had an "unveiling" party at their home for eighty of their friends—ten of mine. This was on a gloriously bright and pleasant day, May 17. I flew out to Arizona again for this occasion, and that it truly was. I can now always look back upon this particular day and feel that at last I know how it must feel to be Grace Kelly!

Well, enough of this drenching Narcissism! Suffice it to say that the portrait project was a thrilling one"totally absorbing"completely destructive to whatever humility I may have once possessed.

In some indefinable way, I have been able to "stop the clock", a feat near and dear to any woman's heart. Probably my deepest enjoyment of this portrait will come many years hence, God willing, when as a frail, bent, and creaking octogenarian, I stand before my really lovely portrait and dare to reflect wistfully that one day I might have resembled ever so slightly the tall, glamorous lady who smiles down at me.

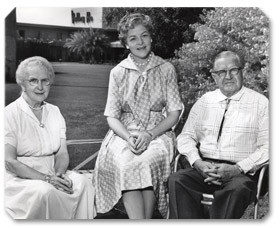

Virginia, at the Valley Ho Resort, Scottsdale, Arizona

An important occasion for Virginia in 1964 was the celebration of her father’s eightieth birthday. Virginia and Carol held the party at their favorite resort, Camelback Inn, and Paul Critchfield, then a student at University of Tampa, flew out for the occasion, which included a surprise unveiling of a pencil portrait of Ken by Robert Harris. It is typical of Virginia’s generosity that she would think to share her own delight in having her portrait done by having a surprise portrait done by the same artist as a birthday gift for her father. A good part of Virginia’s enjoyment of life’s pleasures resulted from sharing them with others, a quality that formalized itself in her philanthropy but which was also present in the everyday life she shared with friends and family.

In early 1964, after her portrait experience, Virginia began keeping steady company with Leslie F. Muter, founder of the Muter Company on Michigan Avenue in Chicago, an electronic parts business that supplied other companies such as Motorola, Inc. In earlier years, Les and his wife, Gladys, had known Paul and Virginia through Motorola, enjoying a light business and social friendship. When Joe Hubata treated Les for his chronic asthma and then over time became Les’s closest friend, the two couples (Les and Gladys, Nell and Joe) became good friends as well. Gladys died suddenly in 1962, and by 1964 Les began to date Virginia, introducing her to the Hubatas’ Joe, Nell, and their daughter, Kerry—on February 4, 1964, at the Drake Hotel. The relationship between the widow and widower quickly grew serious; according to Kerry Hubata, they may have intended marriage. But on October 12, 1965, Les Muter died suddenly of congestive heart failure, a potentially fatal complication of chronic asthma. This sudden loss, shared by the Hubatas and Virginia, bound the new friends in a special relationship that, particularly with Nell, would last over twenty years. Virginia began to spend a great deal of time with the Hubatas, attending shows like Hello, Dolly! at the Schubert in Chicago in February 1966 and inviting them that same month out to the popular Valley Ho Resort in Scottsdale.

Virginia wrote her friends constantly, addressing her letters and cards to “Dearest Chums Three.” Later on, her letters addressed Nell specifically, frequently expressing gratitude for Nell’s friendship. In a letter to Nell from the Valley Ho Resort dated March 1966, Virginia says:

This has been a very different vacation. The detachment and depression have been marked at times with an almost uncontrollable lack of motivation. But I understand this. I have been through it once before, and I do believe a new strength, a new understanding of myself and the future, has begun to take command this week. This sounds selfish, perhaps, this recent inner detachment and self-searching. Perhaps it is, but I guess it was, and is, necessary.

In another letter from the Valley Ho addressed to Nell on April 2, 1966, Virginia writes the following:

One year ago today, I drove Les to the executive depot of this airport, watched that jaunty little blue and white plane roar down the runway, soar upward, wagging its wings in farewell, and point its nose toward a gray and glowering sky. I watched it until it was a tiny speck, with a feeling of foreboding because he was all alone up there, and I knew it would be a grueling trip, which it truly was. How many days, weeks, hours did such hard-headed courage chip away from his life? I wonder. In ten days he'll have been gone six months—half of a year. That's a long, long time.

On the first anniversary of his death, Virginia had a Mass said for Leslie Muter at St. Athanasius in Evanston, the church she had attended since her marriage to Paul. She and Nell, also a Catholic, attended the service together.

Virginia still had long daily hours of deskwork and many board meetings and requisite charity events to attend. On May 14, 1966, as one of seventeen “crusaders” or underwriters, Virginia attended the third annual Saint Francis Crusaders Ball, the entertainment once again provided by one of Virginia’s favorites, now a dear friend, Wayne King, the popular saxophonist. She also attended the Arthritis Foundation Benefit at the Arlington Race Track as an “angel” in May 1966.

On August 20, 1966, Virginia hosted a gorgeous, much-publicized dinner dance to thank all those who had been so kind to her since Paul’s death seven years earlier. In a letter to Nell dated August 6, 1966, Virginia wrote at length of her plans for her upcoming party and of her strong feeling of an enduring connection to Paul.

I love the crisp brilliance of October with its chain of golden days, each an exhilarating promise faithfully kept,each a priceless gift before the long, grey, blustery confinement of winter. I plan to work in solitude on Sunday, charting my guest seating arrangement. This will take a bit of studious concentration, for I am working with 350 people, 35 tables. I cannot begin to describe my mounting excitement. My feeling must be akin to that of a bride or an actress on her opening night on Broadway, and I have the strangest feeling that Paul shares this excitement with me. He so loved parties, thoroughly enjoyed our prebrainstorming sessions. He was wonderfully creative,imaginative; liked to attempt the unusual; considered nothing impossible. I recall once he rented a roulette table from the Chez Paree, which he installed in the dining room, importing a knowledgeable croupier from somewhere to run the game and donating to Saint Francis Hospital any and all funds which accrued to "the House." How he would love and enjoy this party! I feel an unexplainable "partnership" in all my plans, my decisions, and this "psychic confidence" is enormously supporting to me. I sense it strongly, increasingly, in most everything I do now. I believe this is most significantly why I'll not turn to anyone else if it could not have been Les,whom Paul always admired and enjoyed.

Virginia’s dinner dance on August 20 was indeed, with Paul’s “partnership,” a huge triumph, receiving this special notice in the Chicago Sun-Times:

Graciousness Adds Glow to the Party

One of the most gracious parties of recent social history was given a few nights ago by Mrs. Paul Galvin when she entertained approximately 450 friends in the Guildhall of the Ambassador Hotel. What gave the evening its most glowing moment was the brief speech Mrs. Galvin gave when she took the microphone in front of the orchestra and said, "It gives me great happiness to say that I am delighted to see you all. Each one of you has, during the past seven years, contributed in one way or another to make my life happier, and this moment seems the ideal time to tell you so." The guests were deeply moved and many a person said to himself, "What have I done for Virginia Galvin to compare with what she has done for me?" By any standard the party was unique but in a special way it emphasized the fact that a warmhearted, resourceful woman need not become a social cipher just because she has become a widow. Virginia Galvin is beloved by her friends and associates, and her beautiful party was evidence of the fact that she in turn appreciates every gesture of loyalty they have extended to her since her bereavement seven years ago.

Mary Dougherty, August 29, 1966

In the fall of 1966, Virginia began keeping company with Howard Morph, a wealthy Santa Barbara industrialist. In a note sent from Las Vegas to Nell Hubata on October 27, 1966, Virginia wrote, “Howard is charming,a soft-spoken, gracious man, one of the most considerate I’ve known.” This initial trip together was followed by a Christmas trip to Hawaii, then a visit to Santa Barbara in January 1967, where Virginia sent postcards to Nell from the Santa Barbara Biltmore.

On January 21, she wrote:

Dearest Chum, The Biltmore is a lovely hotel, right on the ocean, Spanish in decor, I am having a real whirl and enjoying every minute of it. Howard has scads of charming friends here, and they have been wonderful to me.

On January 23:

Hi, Having a simply scrumptious time, one gay party after another. Tonight I am having one myself, eighteen guests, using the facilities at Howard's club. Ken and Dearie are fine. I talk with them each day. They are happy as two little bunnies at the Valley Ho. This is a wonderful time for me. Keep well, my dears. Miss my daily chats with you.

Love, Virginia.

One can hear Virginia’s elation, her pleasure in being welcomed by new people in beautiful surroundings and perhaps escaping for a time her role as Mrs. Galvin, widow and philanthropist.

Howard’s ensuing trip to Phoenix in February 1967, where he stayed at the Camelback Inn, ushered in a whirlwind romance marked by luxurious travels. Virginia even admitted to Nell, almost breathlessly, that she was being given “the red-carpet treatment.” In May 1967, she accompanied Howard on an extended, elegant trip to Europe, visiting Zurich, Salzburg, Vienna, Como, Paris, and Lucerne. In a postcard dated May 20 from Salzburg, Virginia wrote the following to Nell:

Dearest Chum: Rolling along as though on a platinum pogo stick! Having a simply fabulous time. Beautiful scenery everywhere, lovely accommodations in each spot, delightful traveling companions (especially one!). Lots of laughs and a chance to get better acquainted with a really nice person. Heading for Paris tomorrow and our "finale." Do hate to see this trip come to an end. Hope all is well at home, so anxious to see you.

All my love, Virginia.

Back in Evanston in June, Virginia was briefly hospitalized with a virus, and in an enigmatic note she thanked Nell for her help during a brief period of despair because of her “predicament.” In another letter to Nell dated August 11, 1967, sent from the Santa Barbara Biltmore, she wrote, “I feel a little like the last gal in the skating routine, crack the whip, hanging on for dear life and just barely managing to keep up with the terrific pace.”

In September, returning to Evanston from a fishing trip with Howard to Lake Tahoe and Flat Rock, Virginia worried that Alma, her housekeeper, was unwell, lamented the stacks of unopened mail, and noted that her nephew Paul was off to the University of Tampa. There is a clear reluctance to return to a myriad of waiting responsibilities in her heavy tone. That fall, she was “angel” for fundraising events for The Cradle and the Saint Francis Ball. Most emotionally poignant, nearly eight years after Paul’s death on October 15, Virginia was present at the cornerstone ceremony for the Paul V. Galvin Memorial Chapel and Sheil Center at Northwestern University, blessed by John Patrick Cardinal Cody, head of the Chicago Catholic archdiocese.

In January, she flew again with Howard to Hawaii, then to Tahiti; Pago Pago; Sydney, Australia; and Auckland, New Zealand. Virginia’s flurry of postcards to Nell are filled with dots and dashes of excitement, with a kind of wonder that she was actually visiting such exotic places. The following postcard from Tahiti dated January 29 is a typical representation:

This is a fantastic trip, only one wish, about eighty-nine pounds of luggage less, weather has been very warm, humid. Arriving in Sydney tomorrow, pray it is cooler there, must have hair redone, no choice, but have enjoyed every minute, a new approach to life from here on in, can relax, I find. Ran into Dawn Galvin at lunch today. Truly a small world.

Love and gratitude always, Virginia.

Then in April and May 1968, she and Howard traveled to Europe a second time, touring London, Paris, Germany, Italy, and Switzerland. In August, they went trout fishing along the Snake River in Idaho, followed by yet a third trip to Europe in October, and in December, a vacation in Mazatlan, Mexico. A scheduled trip to Asia was canceled in favor of another Hawaiian vacation in January. On April 12, 1969, Virginia and Howard, along with family members and close friends, attended Carol Critchfield’s second marriage, this time to Chuck Neel, in Paradise Valley, Arizona. Following the wedding, Virginia and Howard went to Las Vegas, and in late April and May, they went on a fourth extensive tour of Europe.

In a cryptic postcard sent to Nell Hubata on May 30, 1969, from the French Riviera, Virginia wrote:

Dearest Chum,

Seems a very long time since I left Illinois and everyone of importance there. Trip going okay. I am glad I have made this journey "tension less" getting some rest. Today we are in Monacoa beautiful spot as is the entire French Riviera. On to Portofino Sunday, then Florence, then Zurich to embark homeward next Saturday. Anxious to see you again and as soon as possible. K has called three times, talked one hour once.

Keep well, all my love and gratitude, Virginia.

From 1964 until the end of 1969, Nell Hubata kept a meticulously organized scrapbook she called Gin’s Tonic. This overflowing book of memorabilia contained all Virginia’s letters, cards, postcards, theater tickets, news clippings, invitations to charity events, programs, and projects Virginia was involved in. Intended as a gift, a “tonic,” from Nell to Virginia, it is a voluminous five year record of a friendship. The enigmatic postcard from Monaco referencing “K” and the desire to return home doesn’t appear until the end of the dozens of letters, notes, greeting cards, and postcards. Notably, there is no reference to Howard, either as an interesting companion or otherwise. Monaco is beautiful, so is the French Riviera, according to Virginia, but Howard is invisible, and “everyone of importance” is in Illinois. What could this have meant?

Paul Critchfield, Virginia’s nephew, tells a story about Kenneth Piper, the vice president of human relations at Motorola’s Franklin Park headquarters in Chicago. When Paul moved to Phoenix in 1968 to work in the human relations department at Motorola’s semiconductor plant on 52nd Street and McDowell, he found out that his Aunt Gin had asked Ken (when he traveled to Phoenix to check on Motorola sites) to please “keep an eye” on her nephew. Ken invited Paul out for a golf game and a bite to eat in the clubhouse afterward and confessed to Paul he was deeply, deeply fond of Virginia. He added that he was aware of his competition but was nonetheless determined to marry Virginia Galvin.

Virginia had confessed the following in a note to Nell Hubata on April 11, 1969, one day before Carol’s wedding and one month before her fourth planned trip to Europe with Howard:

Yes, Ken and I have hit it off in great style. He is fun—a good dancer, quick on the uptake, very pleasant, courteous, attentive, interesting. He returned to Chicago last Sunday, Easter. By that time we'd had four dates (twice at Mountain Shadows). He has called me every night since, and on Tuesday he sent me three dozen of the loveliest long-stemmed red roses I've ever seen. Today I received two white orchids, a corsage for tomorrow. He is returning, as I said, this weekend, and Mex [Wayne King's wife] is graciously including him in her party. So, where are we going? Couldn't say, but it is fun,and enormously rewarding to a gal's ego.

On the day Virginia left Zurich to return to America (Howard had to stay longer on business), someone appeared unexpectedly at the airport in Zurich, offering to accompany her home. Determined to trump his “competition,” Ken Piper utterly surprised Virginia as he stood there, one likes to think, with a bouquet of roses.

Two months later, on July 29, the Hubatas received a handwritten note from Ken Piper, thanking them for the birthday gifts they had given him at Virginia’s recent party. On August 28, one month later, a short note mailed to Nell from Virginia thanked her friend for listening to her confessions during a “topsy-turvy time.” Not two weeks later, on September 9, a small notice appeared in the Chicago Tribune:

Mrs. Paul V. Galvin of Evanston and Kenneth M. Piper of Wilmette, who have known each other for twenty years, have announced they plan to be married early in January. Mr. Piper is vice president of Motorola, Inc., which Mrs. Galvin's late husband founded in 1928. Her stepson, Robert W. Galvin, is chairman and chief executive officer of the company.

Somehow, Howard Morph, after a lavish three-year courtship marked by first-class world travel, including four trips to Europe, lost out in a manner and by means not fully revealed in any saved correspondence from Virginia to Nell or to anyone else. He lost to Ken Piper, a man Virginia had known for years through their mutual connection to Motorola, a man who had been, in fact, a friend of Paul Galvin’s. In four months, from the time he surprised her in the Zurich airport to the date of their wedding, Ken succeeded in doing what he told Paul Critchfield he would one day do, triumph over his competition and marry Virginia.

Ken and Virginia’s marriage, the second for both, took place on December 30, 1969, at the Franciscan Renewal Center in Paradise Valley, the first wedding ever held at the Casa. Father Michael Weishaar officiated; Virginia’s sister, Carol, was matron of honor; and Virginia’s nephew, Paul, now a twenty-three-year-old Motorola employee, was best man. After ten years of loneliness, conscientious work, and a determinedly active social life, Virginia G. Piper’s life had taken a joyous new turn.

Ken and Virginia’s marriage, the second for both, took place on December 30, 1969, at the Franciscan Renewal Center in Paradise Valley, the first wedding ever held at the Casa. Father Michael Weishaar officiated; Virginia’s sister, Carol, was matron of honor; and Virginia’s nephew, Paul, now a twenty-three-year-old Motorola employee, was best man. After ten years of loneliness, conscientious work, and a determinedly active social life, Virginia G. Piper’s life had taken a joyous new turn.

Before Virginia’s second wedding, however, two other significant ceremonies were held. On October 30, 1969, a specially designed plaque for the Paul V. Galvin Memorial Hall was unveiled during the dedication of the Learning Resource Center at Mundelein College. The $300,000 grant for the two-story 350-seat hall had been presented to Mundelein by Virginia on behalf of the Paul V. Galvin Charitable Trust. “I particularly appreciate the privilege of designating this area as a memorial to Paul,” Virginia wrote to Sister Ann Ida Gannon, president of Mundelein College. “His interest in young people was a deep and constant one, tinged with confidence, understanding, and faith. To be able to implement through the charitable trust in Paul’s name the numerous projects which come to our attention is doubly gratifying, for it seems to me that he himself continues to endorse and participate in programs always near and dear to his heart.”

Then, on November 9, Virginia participated in the dedication of the Paul V. Galvin Memorial Chapel at Loyola University’s Medical Center in Maywood, a chapel to be used by patients, doctors, staff, students, and friends of Loyola University Hospital. The ecumenical worship service included a recitation of Paul’s beloved Beatitudes from Matthew 5:1-10, beautifully reflected in the chapel’s new stained-glass windows.

Even after she had married a second time, Virginia would say that she continued at times to feel Paul’s love and guiding presence, that indescribable sense of his ongoing “partnership” in her life. It is tempting to wonder whether among the many reasons Virginia married Ken Piper was his friendship and close work with Paul Galvin. As largehearted and generous a man as Ken was, he would understand, perhaps better than anyone, how Virginia could both love him and still keep Paul in a place of high devotion. Was loving Ken Piper yet one more way of remaining loyally connected to Paul, the man who had begun her life, changed her life, and cultivated all the ideal conditions in which she could come into full bloom? And how would the two marriages differ, the first to an older, wealthy man who was clearly a mentor and an equal partner, the second to a man closer in age to Virginia but who had less money than she did (she sometimes worried over how that might affect his ego), a highly successful man but without the public visibility and prestige of a Paul Galvin?

Virginia clearly loved Paul and cherished his memory, but she loved Ken Piper just as much. With Ken, the social occasions, the friends, and the parties were less formal, looser, and Virginia could relax, feel the weight of the public’s gaze leave her for a time. Paul had been protective of his younger wife, helping her to attain the confidence and assurance she needed in her new life. Now that she had acquired that confidence and gained public stature on her own, Ken would protect her, in part by surrounding her with all the lightheartedness, romance, and gaiety she needed.

Even more importantly, Ken Piper championed Virginia’s philanthropic vision. As she made her new home in Arizona, discovering fresh opportunities for charitable giving, Ken encouraged her to reach for the stars, to bring her leadership and resources to the Valley. He adored Virginia and took pride in her abilities. Virginia would always claim that she and Ken enjoyed a blissful “storybook” marriage. They were utterly compatible, and because of Ken’s strength of character and devotion to Virginia, she was importantly supported in this newest era of her philanthropy.

True to her indomitable and life-affirming spirit, Virginia had emerged from loss and grief to a life filled with a new love, supportive friendships, and a new career. She had become a philanthropic force that would save and enrich lives, particularly in the Valley of the Sun, for countless generations. Forging a path unique to women of her generation by embracing all she had learned from family, faith, and marriage to Paul Galvin, she boldly embarked on an uncharted philanthropic journey that would elicit the highest use of her considerable talents. Intent on service to her community, always advancing values, ethics, and innovations to improve quality of life, Virginia G. Piper became what later generations of philanthropists, both male and female, would aspire to be: an effective, dedicated, inspiring, and visionary leader.