The Legacy

In a letter dated January 3, 1978, Virginia informed her stepson, president of Motorola, Inc., that she was in the process of revising her entire estate plan and will with the help of Robert Williams, president and CEO of Northern Trust, and a trusted estate planner, Foorman Mueller. Her intent was to dissolve the Paul V. Galvin Charitable Trust during her lifetime and to establish a similar trust in her own will. For the next two decades, Virginia’s independent philanthropy thrived, reflecting her own ideals and beliefs, and setting the stage for an organization that would be faithful to the depth, breadth, and values she had supported through her charitable giving.

Ever wise, ever practical, Virginia, in 1995, took the next critical and personal step in philanthropic succession-planning.

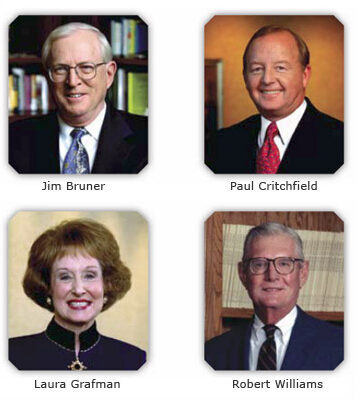

Laura Grafman, executive vice president of Scottsdale Healthcare Foundation, recalled the late summer afternoon when she and the three other lifetime trustees appointed by Virginia—Jim Bruner, her lawyer; Robert Williams, her banker; and nephew, Paul Critchfield—all met Virginia for lunch at Paradise Valley Country Club:

It was a poignant, unforgettable day. Here is the hour Virginia is facing her mortality, saying, “You are the four people I am entrusting with this trust. Let’s sit down and talk.” It was an immensely moving afternoon, and it began with a pledge to do what Virginia had done. We went around the table and each one of us spoke, pledging our loyalty to all she had done. We were very humbled, sitting with her like that. And we never met again. She did not want to meet again; she had passed the baton that day.

Jim Bruner, attorney, banker, and civic leader, who knew Virginia socially for more than twenty-five years and served as her personal attorney for the last seven years of her life, agreed. “The Trust documents were signed at the bank, with witnesses. Virginia was the sole trustee, with four lifetime trustees appointed to direct the Trust following her death, after which this would become the largest foundation in Arizona. Virginia signed all the documents with an inexpensive twenty-nine-cent pen, that was so typical of Virginia. That was also the last day she ever drove her car.” He recalled, too, the moment he heard about Virginia’s death:

My wife and I had just arrived for a vacation in Dublin, Ireland, in late June 1999, and were entering our hotel room, when I looked down and saw an envelope under the door. I immediately had a feeling that it was about Virginia, and it was. The note informed me that she had just died. I was not really surprised, because when I last saw her a few days before, it was obvious that she was in declining health. Virginia’s trust documents named four individuals as lifetime trustees to carry on her work after her death. They were Paul Critchfield, Laura Grafman, Bob Williams, and myself. At her death the responsibility for managing the Trust shifted from her to the four of us. We held our first meeting on July 7, 1999. Our first decision was to begin diversifying the assets in the Trust, which were primarily Motorola stock. Prudent investment policy required us to move quickly to minimize risk to the Trust, which had a value in excess of half a billion dollars at her death. Working with our investment advisors, we developed a plan to liquidate most of the Motorola stock over a thirty-day period. If we had not taken that action when we did, the Trust’s assets would be significantly less than they are today.

From an investment standpoint, our intention was then, and continues to be, to minimize risk to the portfolio by diversification, yet grow by at least enough to cover the annual 5 percent distribution as required by federal law, operating expenses, and rate of inflation. This meant that we would have to earn a minimum of 8-9 percent per year just to keep the trust corpus at the same level to serve the community. For a trust of 500 million dollars we would annually distribute to local nonprofit organizations 25 million dollars, or more as the Trust grew. We knew we would have to be very selective in distributing Trust funds, and sometimes, like Virginia, we would have to make difficult choices.

The four of us met almost weekly for one year after Virginia’s death. All of us had other jobs and responsibilities, but we felt obligated to Virginia to move as carefully, yet as quickly as possible, to achieve her purpose for creating the Trust. The first year required our formulating an investment policy, administrative and distribution guidelines, and an ethics policy; conducting a national search for a President/CEO; and finding office space, just to name a few of the challenges that we faced. During this formative period, we lost one of the original lifetime trustees, Bob Williams. He was replaced by Dr. Art DeCabooter, President of Scottsdale Community College. Virginia and Art had a good working relationship during her lifetime and the other three trustees thought that he would be a perfect fit to carry on the mission of the Trust after the death of Bob.

Even though The Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust is the largest foundation in the state of Arizona, we trustees quickly realized that we could not solve all of the problems of the country, let alone Arizona. We decided to restrict the distribution of Trust funds to nonprofit organizations which serve Maricopa County. The population of Maricopa County (metropolitan Phoenix) is larger than the populations of over twenty-five states, so there are plenty of needs right here in our own backyard. During her later years, Virginia had a similar policy and, except for certain legacy gifts to charities in the Chicago area, gave the vast majority of her funds to those agencies operating in Maricopa County.

The trustees also were concerned about the use of the name “Virginia G. Piper,” and have developed guidelines to monitor this use. We are not interested in using the “Piper” name everywhere but only if will serve the greater good or need of the recipient organization.

The first grants were given about eighteen months after Virginia’s death and were called Cornerstone Grants. They were given to organizations that she had supported during her lifetime. Our goal was to touch various segments of our community, including the arts, healthcare, religion, and a local charity that supports things as basic as providing shoes for a young boy who needs a good start in school. Maybe that boy will gain the confidence to continue school and someday find a cure for cancer. We feel it is important to help those who, through no fault of their own, can’t help themselves. Virginia did that by making a variety of gifts of all sizes, from five thousand to five million dollars, and we felt committed to carry on her philosophy.

To assist in this process, the four original or lifetime trustees thought that by adding additional trustees who had varied backgrounds and professional skills, this process of giving could be enhanced. Over the next several years, three trustees were added: Sharon Harper, Steve Zabilski, and Jose Cardenas. Each of these has brought a new perspective to the vision of the Trust as we continue to carry out the guidelines established by Virginia.

All of us trustees feel the obligation to be good stewards for Virginia. She was a very caring, wonderful person, always concerned about the ongoing welfare of those organizations that she funded. She was genuinely motivated to try to help other people. I once told her, “Virginia, because of you, the people and various charitable organizations in this community that your Trust will support will enhance the quality of life for everyone.” I think this pleased her very much.

While Virginia was a very astute business person and knew the value of a dollar, I’m not sure that she had a true appreciation of her wealth. She would joke, “Now, Jim, is this really a half a billion dollars, with a capital B?” “Yes, it is Virginia,” I would tell her.

We trustees work hard to operate the Trust as if she were still here with us. It will be necessary to pass on Virginia’s values to future generations, because one day all of the original lifetime trustees who knew her well during her lifetime will be gone. The new trustees will then have the responsibility to carry on the wonderful work that was started by this extraordinary person, Virginia Piper.

Art DeCabooter, president of Scottsdale Community College (SCC), who was appointed lifetime trustee after the death of Robert Williams, does not remember a single negative word ever being spoken about Virginia.

She would never seek publicity for herself, and she really studied her philanthropic skills. I’d known Virginia for twenty-eight years and I never in my life saw her disheveled; she was both beautiful and unpretentious. I wonder what the Valley would be like if Virginia hadn’t been here or if she hadn’t been who she was.

We have a nursing program at Scottsdale Community College; I approached Virginia around 1979 or 1980 for endowed scholarships in nursing. Afterward, I heard nothing and decided to just let it be. Then one day an envelope arrived with a letter typed on an old manual typewriter and a check made out to SCC for $50,000.

Another time she telephoned out of the blue. “What’s your favorite charity?” she asked. I talked to my wife, Mary, and called Virginia back. “St. Gregory’s Boarding School in Oklahoma, for personal reasons,” I told her. Well, she sent $5,000 for St. Gregory’s. You never have something like that happen in your whole life, but that was Virginia, a unique, gracious person.

Another time, I was on Xavier’s board, and we needed half a million dollars for a new building. Virginia toured Xavier, and then I went to her home and sat in her living room. She asked questions; I answered. Then Virginia said, “Well, I’ll have to take it to my board, but there’s only one voting member and she’s sitting here in the room with you.” And she wrote a check for $500,000 for an expanded wing of Xavier. She was a very shy, retiring person, never looking for attention but always interested in accountability.

She was very adept with money, very talented, and had a great sense of humor. She would often be the lead gift in a fundraising effort; she would set the bar and few people could match her support. Virginia was a solicitous, caring, insightful woman.

When Virginia Piper’s estate was settled, the Trust received 590 million dollars, making it one of the hundred largest foundations in the nation and the largest in Arizona. In September 2000, the trustees officially opened the doors of the Trust with a small staff, including Judy Jolley Mohraz, PhD, who was hired as president and CEO of the Trust, and shortly thereafter Mary Jane Rynd, CPA, as the CFO. On what would have been Virginia’s eighty-ninth birthday, the trustees awarded eight Cornerstone Grants totaling 41 million dollars. The grants went to a select group of organizations formerly supported by Virginia: Scottsdale Healthcare, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Phoenix, Xavier College Preparatory School, Brophy College Preparatory School, Boys and Girls Clubs of Scottsdale, Phoenix Symphony, Society of St. Vincent de Paul, and Scottsdale Center for the Performing Arts.

By 2005, three other trustees were added to create a total of seven: Sharon C. Harper, Jose A. Cardenas, and Stephen J. Zabilski. From its inception to December 30, 2007, The Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust awarded more than 1,800 grants totaling more than 171 million dollars.

Intellectually curious, vibrantly interested in others, genuine in her compassion for the suffering, articulate in her advocacy of those most in need yet humble in her estimation of her own influence, Virginia did not believe that her wealth entitled her to public visibility and acclaim.

She was a woman who loved deeply and romantically, who had a great sense of gaiety and fun, and who was simple in her faith in God, a woman who came from a modest background, who was principled and hardworking, a woman who took in stray cats, kept friends for a lifetime, and honored her parents, her family, her husbands, and her faith.

Virginia’s true legacy is not to be found on plaques or on lists of impressive donations. Her true legacy lies in the spirit of the hidden gift. Nonetheless, she would be pleased, even honored, if her life,the ways in which she said yes to divine stewardship,encouraged others to say yes to the higher, sometimes harder opportunities for grace in their own lives.

Virginia Critchfield Galvin Piper would probably be most pleased of all if this biography ended not with an emphasis on its subject but with one of her favorite prayers:

Prayer of St. Francis

Lord, make me an instrument of Thy peace;

where there is hatred, let me sow love;

where there is injury, pardon;

where there is doubt, faith;

where there is despair, hope;

where there is darkness, light;

and where there is sadness, joy.

O Divine Master,

grant that I may not so much seek to be

consoled as to console;

to be understood, as to understand;

to be loved, as to love;

for it is in giving that we receive,

it is in pardoning that we are pardoned,

and it is in dying that we are born to Eternal Life.