The Living Room Philanthropist (1975-1999)

Memories

Virginia’s great dream for herself was to have been an author of note, a romantic novelist. With her passion for the written word, she always wanted to write the world’s greatest love story. One day she said to me, “I have an idea. We can just pretend we are authors. I’ll choose the pen name Esmerelda E. Englehardt and your pen name can be Francesca Farrington.” A perfect combination and we were off and running, and for years, we fantasized that we had become two best-selling authors, and it was always a great game between us. I’d call her and say, “I hear you’re autographing your latest book over at Barnes and Noble today,” and she’d say, “Well, I am but I just don’t know if I should have written about that very steamy romantic affair in this book, but I just had to.” It was Virginia’s way of having fun and maybe relieving some of the stress of all her work.

Other times, we’d have “Movie Day.” Virginia just loved movies, especially grand, romantic stories. Sometimes we would take off for a day and go to the Cineplex and just see one movie after another. We would spend the whole day that way, seeing up to four movies in a row. Again, I think it was an escape, temporarily, from the demanding role of being Virginia Piper. She could, for a day, escape into a dark theater and watch movies, travel outside herself into the stories of other people. She just loved that.

Laura Grafman

In 1975, as Virginia G. Piper was privately coping with the death of her second husband, a renewed feminist movement, catalyzed in 1970 by the fiftieth anniversary of the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, which granted women the right to vote, was in full exhilarating momentum. That year, more than three hundred feminist rallies and demonstrations on behalf of women’s rights were held nationwide, and Congress, aware that half of its voting constituency consisted of women, passed legislation on behalf of women’s rights with uncharacteristic and cooperative speed. This new wave of feminism was making an impact within the social institution of the family, in education, religion, the workplace, and in courts of law. Over 50 percent of American women with children were employed outside the home, yet a rising divorce rate feminized the face of poverty as single mothers struggled to raise their children on disproportionately low wages.

The following year, on July 4, America celebrated its bicentennial birthday; later that summer, the Olympic Games were held in Montreal. In November 1976, Democrat Jimmy Carter was elected president of the United States, replacing Gerald Ford, and in 1977 Alex Haley’s Roots aired as an ABC miniseries, drawing a record 80 million viewers, while in Paris the newly opened modern art museum, The Pompidou Center, provoked rancorous controversy. On Broadway that same year, New York, New York and Annie scored long-running hits, music icons Elvis Presley and Bing Crosby died, and the death of Charlie Chaplin unofficially marked the end of the silent film era. In 1977, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Amnesty International, a London-based organization working peaceably on behalf of prisoners of conscience throughout the world, and the world was waking slowly to news of unprecedented species extinction and warnings of vast ecological compromise.

Within the context of a vibrant feminist movement, a bicentennial celebration of America’s history, and an emerging awareness of environmental crisis and heightened sensitivity to world peace, Virginia Piper, who in 1975 was sixty-three and widowed a second time, would begin to move into the most productive and independent decades of her humanitarian service. The philanthropic legacy she single-handedly created, initially founded on work she had accomplished through the Paul V. Galvin Charitable Trust, would eventually impact to an astonishing degree the future of rapidly developing Maricopa County. If what St. Teresa of ovila once said is true, that “suffering is the swiftest route to the Beloved,” then Virginia’s personal anguish over the unexpected loss of Ken Piper may have brought her even closer to her spiritual faith, propelling her into a shining final chapter of prodigious achievement and an era of unparalleled giving by a woman who consciously chose selflessness as her highest response to personal affliction.

While Virginia Piper’s talents and skills had been influenced and developed under the supporting mentorship of both her husbands, her character was rooted in her native intelligence and her family’s loving Midwestern values. At sixty-three, she charted a philanthropic path that was the culmination of her life experiences and flowered from all the support and guidance she had received from Paul, Ken, and her family.

Possibly like no other woman of her era, Virginia was completely adept, trained, and intellectually and spiritually equipped to become a new kind of philanthropist-an engaged, modern philanthropist.

The young woman who had once dreamt of being a writer—the woman who still “tape-sponded” with friends and family and who beautifully and lyrically wrote all her personal and business letters—knew the power of language and communication. She understood that as a philanthropist she could, as an artist would, articulate a vision and oversee its execution and thereby craft an everlasting legacy with ultimate impact.

Imagine a woman who could have easily retired from life becoming single-handedly a one-woman CEO and CFO of a new enterprise devoted to improving the quality of life for Maricopa County citizens. Though it would be years later that the trustees of The Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust would officially designate Maricopa County as the beneficiary of Virginia’s estate, Virginia determinedly set the course for this future.

Though Virginia had advisors and consultants, it is quite clear that she, who valued professionalism, made a conscious decision to redefine charitable giving by being actively and intimately involved in all her philanthropy. This approach was unique for the era, rare among women, and foreshadowed the donor-engaged and directed philanthropy of the twenty-first century.

Imagine a woman who had lost two husbands and who never reared biological children reaffirming that community values, akin to family values, meant embracing people, nurturing a healthy society, and delighting in giving. Virginia was an astute businesswoman who rejoiced in philanthropy. As a savvy professional, she never neglected interpersonal and personal relationships. Her philanthropy wasn’t just professional expression, but it was also the epitome of humanistic expression. Virginia said, “People give to people.”

Imagine a fiercely independent woman settling in a western state experiencing explosive growth and innovation. Virginia loved her adopted Arizona home, and it may well have been that the West, with its open horizons and ever-expanding possibilities, resonated with Virginia’s desire to be liberated from traditional philanthropic giving and from the demeaning stereotype of women adding grace but little intellectual leadership to charitable giving. Virginia, without question, had matured into a powerful, visionary, and effective leader.

The term “living room philanthropist,” as fondly applied to Virginia, derived from the fact that countless people working on behalf of one charity or another found themselves discussing project proposals while seated in her living room, for just as Virginia delighted in sitting with close friends around a kitchen table, she liked to conduct business from the comfort of her home. Handwritten checks in generous amounts frequently emerged from these living-room discussions.

It was Virginia, in her quest for exactitude and excellence, who judged the merits of every request and, amazingly, wrote and typed all her professional correspondence. Virginia would type, “My board has considered your request,” but Virginia was the board, just as she was “kb,” Kitty Brandleknees, the secretary typing hundreds of business letters on her manual Royal typewriter.

Virginia worked long hours—often late into the night and seated at a huge desk in her homey but cluttered office-with her beloved cat, Gus, keeping her company as he reclined among her papers, napping on unanswered letters. She answered dozens of phone calls and piles of correspondence daily and attended a constant round of meetings and charity events.

Because of the extent of her wealth and the depth and breadth of her charitable contributions, Virginia Piper’s public prestige was tremendous. Worthy but incessant requests for monetary aid had to be answered with discernment, so Virginia’s financial acumen, common sense, and nearly intuitive ability to sort through massive correspondence became crucial factors in her decision process.

the theater cat, in the musical Cats

When Virginia and Ken moved to Arizona in 1972, Maricopa County’s population had been just under one million. By 1999, the year of her death, the population had increased to more than three million. The cultural and social needs she encountered upon first arriving multiplied in proportion to the population increase, and from 1975 on, Virginia found herself at the forefront of a new, pioneering philanthropy in Arizona. Looking back over the diverse list of Virginia Piper’s contributions from 1975 to 1999, it is nothing short of staggering to realize the full extent of her influence upon the cultural, educational, medical, and religious sectors of an entire county, affecting in turn an entire state, perhaps even the West itself.

Over a period of twenty-five years, Virginia funded over a thousand grant requests. Post-widowhood, she chose a path of active selflessness, blooming into a happy, generous, self-actualized woman. Children, education, arts and culture, healthcare and medical research, religious organizations, and older adults became her focus. While these areas of interest had been part of Paul Galvin’s earlier charitable initiatives, Virginia devoted herself to these causes, bringing her own unique stamp and approach. What Virginia didn’t know, she learned. Her lifelong habit of mind, devotion to study, and work ethic served her well, and it soon became clear to the Arizona community that Virginia Piper’s investment in a cause meant the individuals and organizations had been thoroughly vetted and researched. Her reputation as a philanthropist was simply impeccable.

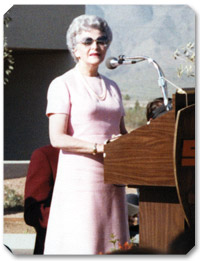

Kenneth M. Piper Family Health Center, Scottsdale, Arizona, 1977.

Virginia understood, too, the power of her name and how her reputation could benefit a cause. Someone once said, “If it’s good enough for Virginia Piper to invest in, it’s good enough for me.” While Virginia said “yes” to many people and organizations soliciting funds, she never once hesitated to say “no” to proposals she deemed unworthy or unworkable.

Virginia saw herself as a catalyst for community engagement. Time and again, Virginia’s leadership meant reaching out to other community leaders and using her funds to inspire more giving. Social events, while satisfying for their own sake, also meant, for Virginia, networking, reconnecting with people who could make a difference for Arizona citizens.

the Virginia G. Piper Special Care Unit at

Scottsdale Memorial Hospital in January 1984.

For example, Virginia adored children. Betsy Taylor, founder of Crisis Nursery, Inc., accompanied Virginia on her first site visit to the nursery, a place of respite for abused and neglected children. A little boy of about three, feeling bold and sensing Virginia’s loving nature, went up to her and tugged her skirt. The child was covered with cigarette burns. Virginia reached down and scooped him up into her arms. The two held on to each other. This moment reinforced Virginia’s commitment to children and the Crisis Nursery in particular. For years, she underwrote their Annual Gala Benefit and contributed to their fund drives.

Scottsdale, 1991

Virginia knew that abused and poor children needed a safe, nurturing environment in which to play and to build their characters. Prior to the merger in 1991 of the Boys Club and Girls Club, Virginia managed to support both. For the Girls Club, she provided clothes for their thrift shop, sent personal contributions, and gave financial support for a new facility. In 1992, Virginia spearheaded the fundraising by contributing a million dollars to complete a new building that would house the Scottsdale Boys and Girls Club. True to her hands-on involvement, Virginia previewed and discussed plans for the new buildings, fully aware of the need for quality, to serve the multiple needs and interests of Scottsdale children.

Similarly, Virginia advanced education and arts and culture in the Valley.

She greatly admired Russell Nelson, PhD, a former president of Arizona State University (ASU). The two had a chemistry of vision that flourished during the planning and execution of the Paul V. Galvin Playhouse in the College of Fine Arts at ASU in 1989. Virginia actively assisted in the national adjudication process that resulted in the selection of the internationally known architect, Antoine Predock. Virginia thoroughly enjoyed reviewing all the submitted models for the proposed theater. She was very proud of the project and gave her heart and soul to supporting it. She knew the Paul V. Galvin Playhouse was important to the university and the Valley, and a testament to her loving memory of Paul Galvin. When the playhouse was completed, Virginia had a second portrait of herself painted by Robert Harris and today it hangs in the Galvin Playhouse lobby alongside a portrait of her first husband, Paul Galvin. While Virginia gave one million dollars to create the Galvin Playhouse, records indicate that she contributed to ASU frequently, and the university honored her on several occasions.

Virginia’s family home had been filled with music, and Virginia never lost her love for live musical performances. She played the organ and the ukulele, and loved to sing harmony. With characteristic flair, she became a terrific arts advocate and enjoyed bringing great entertainers to Arizona. For almost a decade, she underwrote performances for the Scottsdale Center for the Performing Arts (SCPA) Gala. Because of Virginia’s generosity, the SCPA Galas reaped exceptional proceeds from these events. Tommy Tune, Bobby Short, Michael Feinstein, Dionne Warwick, and Marvin Hamlisch all came to the SCPA, and Virginia, beautifully dressed, had a marvelous time listening to great talents and visiting with the artists after the show.

Unquestionably, music comforted Virginia and brought immense joy. She and her sister, Carol, both enjoyed attending the Phoenix Symphony, sitting in their box, the first on the left. It was from this box that Virginia would wave graciously to the conductor and the musicians who sincerely appreciated her million-dollar challenge grant for community members to match in order to double her contribution for the Now for the ’90s Phoenix Symphony Stabilization Campaign. Her gift, according to Howard McCrady, then President and CEO of the Phoenix Symphony, was “the largest in [their] history.” Virginia, in a letter dated February 12, 1990, wrote: “I have gratefully observed that this so-called ‘leadership grant’ has, as predicted, prompted others to follow suit!”

During Virginia’s lifetime, she also funded refurbishments of the Scottsdale Center for the Performing Arts theater and of the Phoenix Boys Choir Concert Hall. For nearly twenty-five years, Virginia faithfully contributed to the Arizona Kidney Foundation to support their Annual Authors’ Luncheon, an event that Erma Bombeck founded. Virginia’s front and center table was a visible testament to her interest and involvement in this cause. Virginia respected and admired Erma and Bill Bombeck. When Bill called to request one million dollars for the new office building of the American Red Cross, she immediately said yes.

opening of the Virginia G. Piper Special Care Unit at Scottsdale Memorial Hospital, Osborn

More than anything, Virginia loved seeing people progress. Each generation, in her view, should have greater opportunities for a better life. Fundamentally, she saw herself as a servant to civilization’s progress. Her great ability to empathize with others across class, racial, and ethnic lines—her ability to embrace all people and to see each and every one as an expression of the divine- motivated her. While Virginia was lucky enough to have nearly a half billion dollars to effect change, she was smart enough and compassionate enough to want to make the world better—not in the abstract but in concrete ways. Her giving was always strategic and integrated.

Perhaps most importantly, Virginia understood how healthcare was integral for a healthy society. Her sustained support of Scottsdale Memorial Hospital (now Scottsdale Healthcare) was invaluable to a growing community.

When north Scottsdale was a rural landscape, more desert than family plots, Virginia nonetheless foresaw the need for healthcare services in a community not yet fully populated. Early in the 1970s, she and Ken encouraged Motorola to invest a quarter of a million dollars in the growing hospital. Upon Ken’s death in 1975, she invested in the creation of Scottsdale Memorial’s Kenneth M. Piper Family Health Center. During Virginia’s lifetime and because of her sustained giving, the health center expanded from its original 8,700 square feet to become, eventually, the comprehensive 32,000-square-foot Piper Outpatient Surgical Center.

Virginia was among the early advocates for better, cutting-edge “whole” patient care,but again, inclusiveness was important to Virginia. Whether young or old, rich or poor, Virginia never forgot the diversity of her community. When Virginia was approached for a major gift to support adding a second floor for overnight outpatient services for the Piper Outpatient Surgical Center, she immediately asked about pediatric surgery. Assured the center would provide childhood-to-senior surgical care, she contributed to the building facility fund.

Virginia’s major gifts (particularly in healthcare) received much publicity. Virginia only accepted such attention because she shrewdly recognized how publicity generated community awareness and “challenged” others to support worthy causes. Virginia always focused on impact and people. Time and again, she spoke with nurses and doctors, always asking, “Do you have what you need to do your job well?”

Virginia also became interested and involved in Esperanza, a nonprofit international health organization based in Phoenix and directed by a Franciscan brother and general surgeon, William Dolan, MD, who organized volunteer doctors and surgeons to provide medical care in the Amazon. Virginia was thrilled to assist, recognizing that in many areas throughout the world, basic healthcare was nonexistent. Combating childhood intestinal parasites, polio, infections, and starvation in the Amazon paralleled Virginia’s efforts for supporting impoverished families in Arizona.

Until her death in 1999, Virginia deepened her charitable focus on religious life and the impact of religion in society. She gave funds, in Phoenix, to both Xavier College Preparatory and Brophy College Preparatory, again, integrating her charitable foci. Faith, education, and adolescent well-being were all advanced by her commitment to these Catholic schools.

On June 24, 1993, at Xavier College Preparatory, the Virginia G. Piper Center for Science and Computer Studies opened. Virginia was the major contributor to this effort, and in the foyer, her sister Carol’s painting of a “colorful, floral desert scene” graces the wall.

Virginia also significantly supported Brophy College Preparatory scholarships and never failed to donate auction items for fundraising. Seeing young people thrive educationally was a passion for Virginia.

For decades, Virginia supported hundreds of students seeking a college education at various American colleges and universities. Many of the students were first-generation college students. Once again, Virginia, the philanthropist, was ahead of her time in providing college funding for many individuals-including returning female students who had become widowed, had interrupted their schooling to marry and raise a family, or had divorced and lacked the educational skills to support their families.

Students sent grateful letters, reports of their grades, and biographies about happy (and sometimes unhappy) childhoods, and Virginia answered each and every one. With Virginia’s demonstrated faith in them, these students thrived, aspiring to become elementary teachers, family law specialists, and social workers assisting the disabled and urban disadvantaged youth.

It is impossible to know how many students Virginia helped, since many students received funds anonymously. Records clearly indicate, however, that Virginia’s largesse might have extended to nearly five hundred students, approximately twenty to thirty a year. For every student she helped, she affected not only the student’s life, but also that of the student’s family. Thus, one well-educated parent sustained generations.

While Virginia “schooled” others, she also “schooled” her community. Ahead of her time, Virginia held educational salons in her home, inviting experts in various fields. She’d invite friends to her home for lunch, a lecture, and discussion, often followed by a swim in her lovely pool. Long before the phrase “lifelong learning” had been coined, Virginia practiced it. Virginia also fervently supported the Catholic Diocese of Phoenix, pledging untold amounts for aid to the poor, church community services, and outreach to underserved communities. She gave generously to St. Philip the Deacon Catholic Center, a mission church in the heart of an inner-city ghetto in Phoenix. Other churches she supported in Scottsdale and Phoenix included St. Maria Goretti, St. Joseph’s, and Our Lady of Perpetual Help.

Her total renovation of the chapel at the Franciscan Renewal Center (“the Casa”) established the Paul V. Galvin Chapel in remembrance of her first husband. This chapel was, undoubtedly, one of her most beautiful and happiest achievements. Virginia started her morning at the chapel for 7:00 a.m. Mass, enjoying a respite from cares, relishing the solitude and a place to pray and remember both Ken and Paul.

Long before discussions regarding “geriatric care” became commonplace in American life, Virginia was actively supporting senior care. Roman Catholic Bishop James Rausch asked Virginia to spearhead support for the Foundation for Senior Living. She tapped Laura Grafman to assist her in enlisting community women, who formed Friends of the Foundation for Senior Living and created many successful fundraisers for older adults.

Kenneth M. Piper Family Health Center in 1976

Perhaps Virginia was called to support elders and youth because of the belief that a civilization can be judged by its care of its most vulnerable populations. Perhaps too, because of her family, Virginia understood well the progression of parents as caregivers to elders needing care. Perhaps it was her faith that made her honor human life during all its stages. Or perhaps for all these reasons, Virginia had the foresight to invest in senior care at a time when such care had not yet received national attention.

It is impossible to capture the full extent of Virginia’s living room philanthropy. The anecdotes given here are just a few examples of her visionary and compassionate philanthropy. Virginia, once engaged in any cause, gave multiple times in multiple ways over a sustained period of time to ensure its success.

The Arizona Republic, the Scottsdale Progress, and the Scottsdale Scene magazine all agreed that Virginia was one of the most important philanthropists in Arizona. Unlike the East and Midwest charitable social circuit dominated by families from the Social Register, the West was more inclusive, thanks to leaders like Virginia.

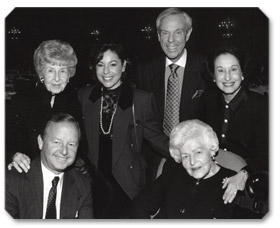

dinner party honoring her philanthropy held at the home of Laura and Dayton Grafman

Recalling the success of the annual Crusaders’ Ball, a black-tie event for Saint Francis Hospital in Evanston, Illinois, that brought physicians and the community together for an evening of dinner and dancing, Virginia suggested a similar event to the administrators of Scottsdale Memorial Hospital (now Scottsdale Healthcare) as both a great community builder and a fundraising opportunity. Fully underwritten by Virginia in 1979, this black-tie event, the Honor Ball, was the first of its kind in Scottsdale. More than thirty years later, the Honor Ball is still a flourishing and successful event that specifically honors an individual or group whose philanthropy has had a dramatic effect on the healthcare system.

Over time, Virginia’s workload took on crushing proportions.

Anyone possessed of such extensive wealth could have lived more extravagantly than Virginia and with far less dedication to others. She could have declined the work of carrying on Paul Galvin’s charitable trust, or she could have simply fulfilled that one promise, a giant task in itself, and then chosen to live her final years following Ken’s death traveling the world, luxuriating in glamorous homes and circumstances. As an independently wealthy widow, she could have bought and enjoyed nearly anything on earth, but Virginia chose to remain in the same pleasant but unpretentious home she and Ken had chosen and shared together, to drive the same 1986 Cadillac, and to save things, from rubber bands to ball gowns, in case they might be used again or given to someone who needed them. Her fortune, which she had always viewed as Paul Galvin’s, was a means to a far greater end than mere personal gratification. True, she had been deeply influenced by the values of her grandmother and by both of her husbands. Yet in each of our lives, the choice is solely ours how best to spend our hours, give our gifts, and count our blessings.

Virginia devoted the last phase of her life almost entirely to sharing her wealth, time, and heartfelt empathy for those in need. In a career spanning nearly half a century, Virginia struck an admirable balance between a public life of philanthropic visibility and a private life of personal simplicity, and her use of her own wealth to raise the quality of life for countless others made her a tremendously powerful role model. She exemplified a woman of “unselfed” grace anchored in financial acuity, diplomatic tenacity, and independence of vision.

Even in an era of self-determinant feminism, her life bore more weight in terms of what she chose to do for others than most. In the closing years of the twentieth century, as Virginia’s physical health waned, women’s authority in America had expanded to include nearly every aspect of public leadership. The Equal Rights Amendment had suffered defeat, gender discrimination and salary inequities still existed, and in the wake of a feminist backlash, some had even declared the movement dead. Still, college-aged Americans enrolled in women’s studies courses, while ecofeminist and other grassroots organizations took on diverse forms and influences, proving feminism to be not only alive but adaptable and responsive to new issues and concerns of women. Virginia’s work and her legacy were supported and upheld by this environment of increasing public feminist influence.

Eventually, Virginia’s self-imposed workload and the inevitable process of aging began to exact their tolls. In the early 1990s, she fell several times, accidents occasioned sometimes by her beloved cat, Gus. Meanwhile, degenerative neurological problems began to present themselves, and by 1995 her health had become so compromised that she chose to remain at home. Virginia had perfected a poised, public persona, but by 1995, when she was no longer able to maintain that persona, in accordance with her temperament she chose to recede from public view with dignity. She spent the last few years of her life attended by her longtime companion and devoted housekeeper, Helen Dusch, as well as a small cadre of dedicated nurses. As a solitary child in rural Idaho, Virginia’s companions were composed mainly of animal friends. In her final years, confined to her home, Virginia’s solitude once again included animal companions, but it was also blessed with family, relatives, and friends who daily expressed their love and appreciation of her kindness, generosity, and grace.

Near the end, Virginia spoke daily, reverently, of her grandmother, Cora Higley, and of her first husband, Paul Galvin. She quoted Cora’s gentle Christian Science tenets, blending them without conflict into her Catholic faith. Virginia had never been one to hold theological debates with herself or with others. Her spirituality was simple, practical, and inclusive, but her conversion to Catholicism in 1948 had influenced several of those closest to her to convert as well: her nephew Paul, her sister Carol, and friends Laura and Dayton Grafman. Both of Virginia’s husbands were also practicing Catholics, as were many of her intimate friends, including, among others, Sister Ann Ida Gannon, Gladys Leach, Sister Mary Cyril Tirpak, the Hubatas, Father Michael Weishaar, and Father Frank Fernandez.

and Dayton Grafman on the way to the

Weston Priory in Vermont

Virginia had been a faithful daily Communicant, but in her final years, when she could no longer attend her favorite parishes, Bishop Thomas J. O’Brien came often to her home to celebrate Mass with her. Father Frank, too, a close friend and confidant, visited Virginia each Sunday to conduct Mass just for her. Many of those who remained close to Virginia in her final years came from the religious side of her life.

Critchfield, Bishop Thomas O’Brien, and

Claudia Critchfield

Virginia did not press her spiritual beliefs on others. She did something far more challenging: she lived what she believed. Her life can be viewed as an ancient, archetypal tale-the hero’s journey-a tale told worldwide in multiple guises, showing how to live beyond oneself, forging from flesh and temporality something enduring and fine. If the journey into selflessness were less arduous, Virginia’s life might not present such an uncommon example. And certainly, self-reward could not have been Virginia’s primary motive, nor her love of parties, or her enjoyment of social, charitable, and cultural events, though,despite innate shyness stemming in part from an isolated early childhood,Virginia did greatly enjoy these things.

Critchfield, and Dayton and Laura Grafman.

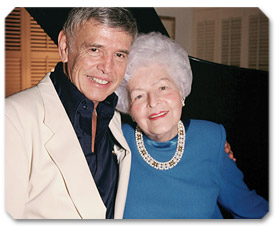

(Bottom row from left) Paul Critchfield and

Virginia at “Keys to the Future” fundraising event for Arizona State University School of Music

Instead, her primary motive can perhaps be attributed to a faith inspired initially by her grandmother’s belief in Divine Truth and later by Paul, who kept a copy of the Beatitudes on his desk. Faith gave her the composure to bear the often taxing contradiction between isolation and celebrity. Virginia’s spiritual convictions were the bedrock of strength she needed. She lived her faith the way she practiced her philanthropy, daily, enthusiastically, profoundly.

After several years of increasing debilitation and declining health, Virginia Piper, a woman who had contributed millions of dollars to healthcare and medical research but who only reluctantly took medicine herself, died at the age of eighty-seven. In the early morning hours of June 14, 1999, at her home in Paradise Valley, Virginia G. Piper was, according to the tenets of her Catholic faith, “risen in Christ.”

Her last words were spoken to Carol, whose paintings Virginia had hung throughout her home. As Virginia’s only sibling and closest confidante, Carol Critchfield had shared a unique place in the life of her older sister. As lifelong best friends, they called each other four and five times a day. So, as Virginia, days from death, lay on her bed in her home in Paradise Valley, her last words were addressed to Carol, the little sister she had fiercely protected and deeply cherished.

“We have talked enough. That is all.”

History suggests that society manages to create its necessary leaders, but history also suggests there is often a vanguard of individuals who pave the way and forecast a new way of being in the world. Virginia G. Piper, through loss, opportunity, and upbringing, paved a path for both women and men to engage in more modern approaches to philanthropy. Virginia believed the best philanthropy was visionary, strategically integrated, and strengthened, if possible, multiple goals. Through her constant interest in children, education, arts and culture, healthcare and medical research, religion, and older adults, she wove an interconnected network of support that would provide the greatest social, educational, and cultural benefits. These benefits were not just intended for her lifetime but for all time.

Virginia inspired (and still inspires through The Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust) individuals and communities to give.

Philanthropy, at its core, is love for humanity. Joyfully, Virginia embraced and encouraged others to embrace the personal and the communal affirmation of giving. Because Virginia lived her life so well, millions of Maricopa County citizens lead a better life. Virginia continues to inspire and aid us all. Future generations will be healthier, better educated, and live in a county that values arts and culture and believes in the spiritual and communal power of giving.